Ariks purchased by missionaries, subsequently the grandfather of Papuan missionaries, activists and politicians

Jonathan Ariks, bought from captivity among the Meyah people by Dutch missionaries at the age of eight in 1881, would later become a helper/teacher of the missionaries and the father and grandfather of important Papuan missionaries, activists and politicians.

1. Abstract

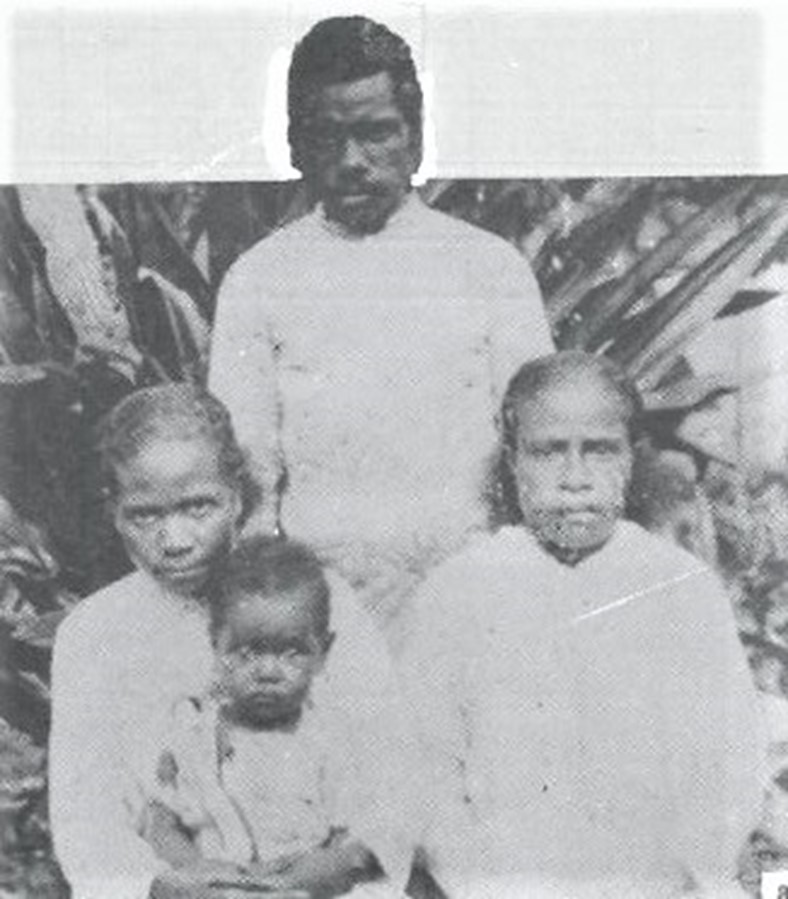

Born among the Kebar people in the mountains of the Bird’s Head Peninsula in Dutch New Guinea, Jonathan Ariks was sold to and adopted by the Meyah people after his father had been accused of sorcery. He was bought by Dutch missionaries Johan and Wilhelmina van Hasselt on 8 January 1881. The missionaries considered this a redemption from slavery. He was first named Januarius and later baptised Januarius and soon became the Van Hasselt’s most trusted stepchild and teacher-assistant in their missionary work. Later on, he founded the first Papuan Mission Support Society. He married another stepchild of the Van Hasselt family, called Paulina; their son Johan and daughter Marietje and their descendants would become central in the political struggle for New Guinea’s independence from Indonesia. The caption underneath the photograph reads: ‘Jonathan and Paulina Ariks, Marietje (later married to W. Rumainum). On the right: the later Njora Kafiar’.1

2. Timeline

3. Jonathan Ariks’ story

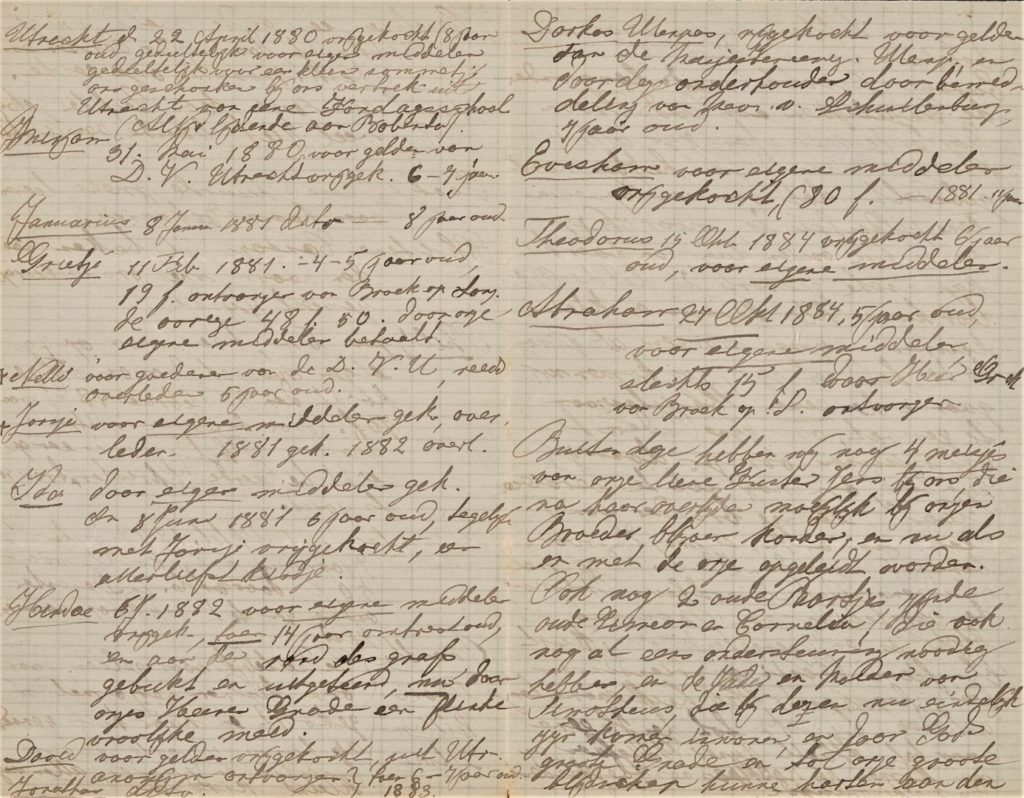

Source 1: Purchase agreement

Transcription and translation:

Utrecht, d. 22 April 1880 redeemed (8 years old), partly by means of our own funds, partly by means of a small sum from a Sunday School, offered to us when we left Utrecht. (Always suffering from Bebento [a serious and infectious tropical skin disease, GM];

Mirjam 31 May 1880 redeemed for money from D. V. Utrecht, 6-7 years old;

Januarius d. 8 Jan. 1881, 8 years old;

[etc.]

I found a reference to Januarius and other children in a letter from missionary wife Wilhelmina Van Hasselt-Mundt, stationed at Maninsinam in Doreh Bay in Dutch New Guinea, to the women’s Mission Support Society in The Hague, 6 February 1885.2

This letter is held in Het Utrechts Archief (the Utrecht Archives) under the category ‘Ingekomen brieven bij De Haagsche Hulpvereeniging van de Utrechtse Zendingsvereniging (UZV) (“Haagsche Dames Comité”), afkomstig van (echtgenotes van) zendelingen in Nieuw-Guinea, (1862) 1864-1910’, file number 2200-5 Nieuw-Guinea, 1885-1901; this page was digitised as NL-Uthua_a342542_000050.jpg.

The archives of the protestant missionary society De Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging contain information on the work of this organisation both within the Netherlands as well as ‘overseas’, particularly in Dutch New Guinea (from 1862). From 1900 onwards, the organisation started to cooperate with, and finally merged with, other Protestant missionary organisations. Archives pertaining to their specific missionary fields – such as New Guinea – can be found in Het Utrechts Archief, 1102-1 and 1102-2, Raad voor de Zending, mostly under the heading of Utrechtse Zendingsvereniging.3

For a large part, the material consists of mostly handwritten minutes of meetings, board minutes, correspondence with the government, as well as with members and contributors, yearly gatherings and yearly (financial) reports; during the twentieth century, the material is increasing typed (on very thin, fragile paper). Not all correspondence from New Guinea has been kept, in particular the period 1862- 1900 is lacking. Therefore, the correspondence between the missionary wives and the women’s support organisation is an important source for the first European settlement contact with the local people of Northern Dutch New Guinea. The women told stories about some of the children they bought, but the overview in the letter shown here is an exception.

It is not possible to find the original names of the children once they were bought by the missionaries; as can be seen from the example, the children were immediately renamed when they were bought, sometimes with references to the people who had offered the money (such as ‘Utrecht’ after a Sunday school in Utrecht) or to the month of the purchase (‘January’). After this initial renaming, often a second renaming took place after baptism and confession; this makes finding references to a single child even more difficult. Nor do we know exactly from which tribe or region the children originated – sometimes this information pops up as a fragment in a story.

The voice or perspective of those who were targeted by this mission is as good as absent. Information about individual Papuan children and their life courses (sometimes as adult Papuan Christians) can only sometimes be partly retrieved by carefully stitching together fragmentary evidence from various sources, published (see below) and unpublished (this archive). This is possible only for those who ‘stood out’, the promising children bought by missionaries (until 1900) or missionary helpers in the period between 1900 and 1962.

Working with these archives requires the capacity to read Dutch and old Dutch handwriting; as of yet, there are no automated digital transcriptions available (and therefore also no automated translations possible). A small selection of this archive has been digitised, more will probably follow over the next five to ten years.

Source 2: Anthropological writings

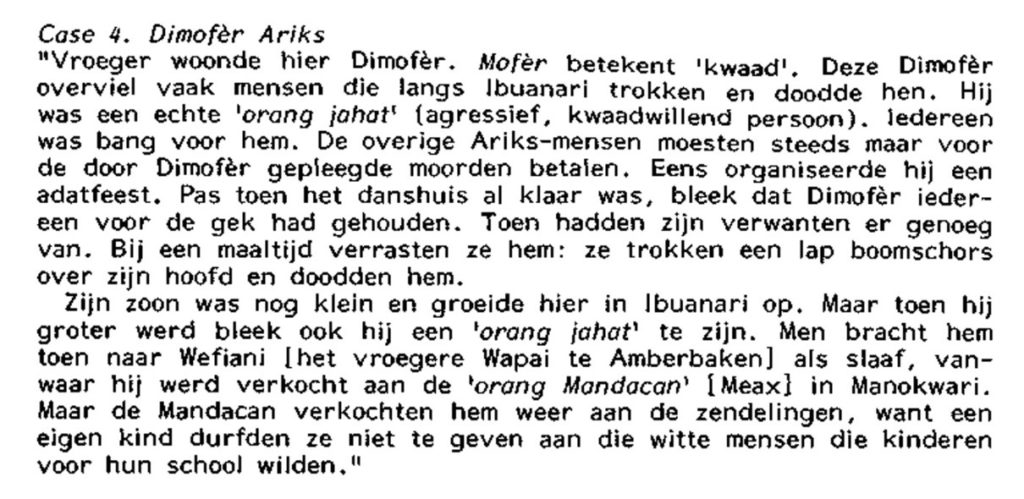

Another reference to Ariks is found in the research of the anthropologist Jelle Miedema, who was interested in the story of Jonathan and Johan Ariks as he was intrigued by the tribe’s name ‘Ariks’, which he knew to belong to the Kebar people. Asking after the fate of Jonathan Ariks, they told him the following story:

Case 4, Dimofèr Ariks

‘In the past Dimofèr lived here. ‘Mofer’ means ‘evil’. This Dimofèr often ambushed people passing by Ibuanari and killed them. He was a real ‘orang jahat’ (aggressive, malicious person). Everyone was afraid of him. The other Ariks people always had to pay for the murders that Dimofèr had committed. One day he organised a ritual gathering. Only when the dance house was already ready, did it turn out that Dimofèr had fooled everyone. Then his relatives had had enough. At a meal, they surprised him by pulling a piece of barkcloth over his head and killed him.

His son was still small and grew up here in Ibuanari. But when he grew up he too turned out to be an ‘orang jahat’. He was then taken to Wefiani [the former Wapai at Amberbaken] as a slave, from where he was sold to the ‘orang Mandacan’ [Meax people] at Manokwari. But the Mandacan sold him to the missionaries again, because they did not dare to give a child of their own to those white people who wanted children for their school.4

Jelle Miedema’s doctoral thesis on the history and anthropology of the people on the highlands and plains of the Bird’s Head Peninsula of Papua New Guinea offers very rare oral evidence from Papuans as to the reason why a child from a Papuan people (in this case, the Kebar) was sold. As becomes clear from this excerpt, Dimofèr’s son – who was part of the Ariks clan – was sold to another tribe, the Meax or Meyah. Miedema’s study demonstrates the existence of adoption systems among several Papuan peoples. Gilles Gravelle confirms these findings with a detailed study of the people who initially adopted Dimofèr’s son, the Meax or Meyah. These studies suggest that the system worked to restore imbalances due to differences in family sizes or gender imbalances, which could have severe consequences for a family’s standing or material well-being. This could happen within a clan, but also in the case of power imbalances between clans. Indeed, the relatively rich Meyah people often bought children from other peoples. According to Gravelle, these children could be accepted as ‘nuclear family’ members, but could also be exploited and treated badly. The fate of the child lay in the hands of the new owner.

Jelle Miedema further explored the Ariks family in ‘Bijlage 2’ (Appendix 2) of his doctoral thesis5. Jonathan’s son Johan Ariks was educated as indigenous missionary-teacher at the protestant seminary at Depok (Java). Later he became an important political figure fighting for the independence of West Papua, as detailed below.

Miedema’s dissertation offers a very detailed and rare historical-anthropological description of the area. It is exceptional in scope – covering more than one tribe within the region – and gives a long, in-depth historical overview starting from the very first Dutch colonial interferences in the region based on original source material. At several points he discusses the position of children within kinship systems, as adopted children, but also as objects of negotiations between tribes, as captives of war, or as slaves.

Miedema undertook this study in the service of the Evangelical Christian Church of Irian Java, supported by the Raad voor de Zending van de Nederlandse Hervormde Kerk. This specific entrance to the ‘field’ should be kept in mind but did not prevent Miedema from being critical of the missionaries in whose footsteps he followed. ‘Bijlage 2’ contains several incorrect statements about Jonathan’s position among the missionaries, because Miedema mixed up two different Papuan children with the name Jonathan. Careful comparison of published and unpublished missionary sources has led to the conclusion that Januarius really was Jonathan – Dimofèr’s son.

Source 3: Berigten van de Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging

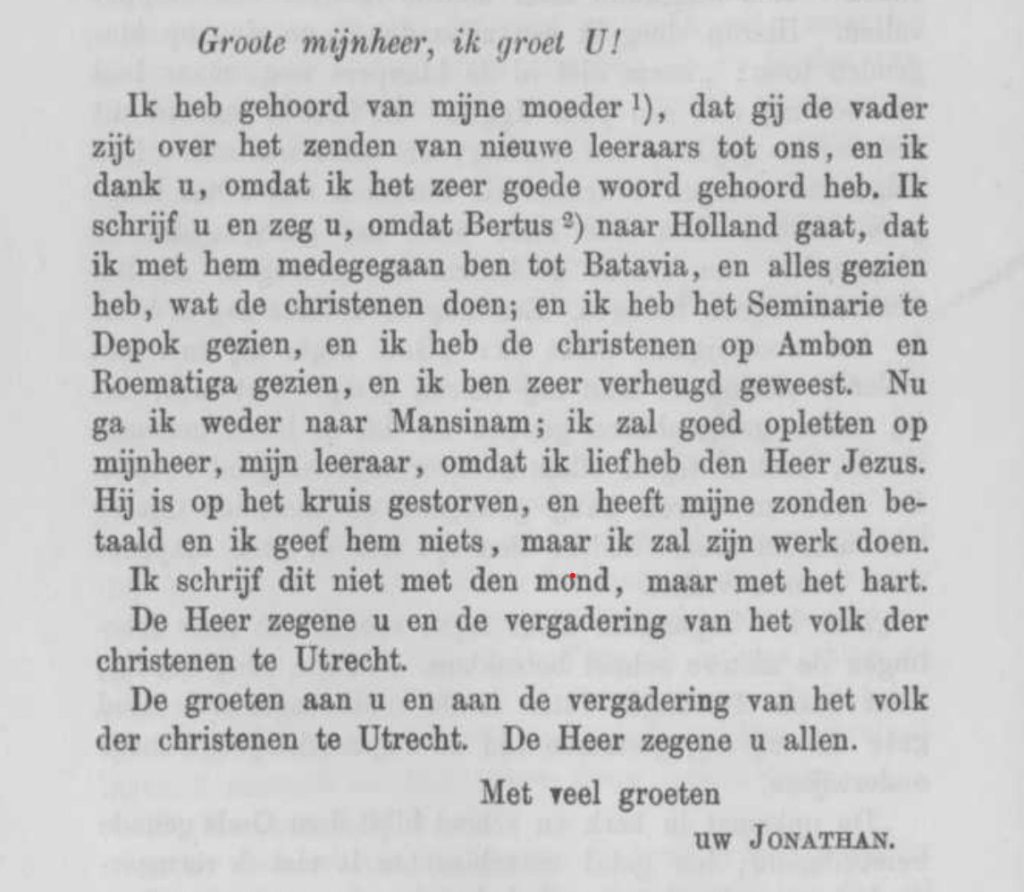

This letter, written by Jonathan to the director of the Utrechtsche Zendingvereeniging, was published in the Berigten van de Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging6

The Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging (Utrecht Missionary Society) published two journals, the Berigten van de Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging (BUZV, for adult members of the society) and Het Penningske (for the youth). Het Penningske – directed at the Dutch youth – contains somewhat more information about indigenous children. Sometimes individual issues even feature a complete story of one exemplary indigenous child.

The BUZV contains fragments of stories about the children the missionaries bought and raised in their households. These may contain pieces of the history of their purchase, of the first ‘successes’ in terms of adaptation to a missionary household or understanding Christian religion or values, mentions of baptism or confession, worries about illness, stories of their deathbed (and the measure of their belief) and announcements of their death. Sometimes, problems were mentioned (running away, difficult characteristics, disputes, refusals) but mostly positive elements were selected. In comparison to unpublished letters and diaries, resistance, problems and failures are barely mentioned in the journal. Neither the considerable work the children undertook, nor the fact that they were easily exchanged between missionary households can be derived from these journals.

The journal’s narrative is clearly framed as a narrative about pious heroes who sacrifice their lives to save the poor, ignorant heathen people, children in particular. It does stress the difficulties faced by missionaries to show the measure of sacrifice, but balances this with sufficient ‘successes’. The fate of the missionaries could be easily followed by the journal’s readership; the life courses of the children could not. It is difficult to stitch together a life course from the fragments offered. Together with letters and multiple journal issues it is possible to reconstruct at least some lives of ‘adopted’ children. Because Jonathan and his children Johan and Marietje did relatively well, they were relatively often mentioned.

Source 4: Depok Archives: Johan Ariks, the son of Jonathan and Pauline Ariks, educated at Depok

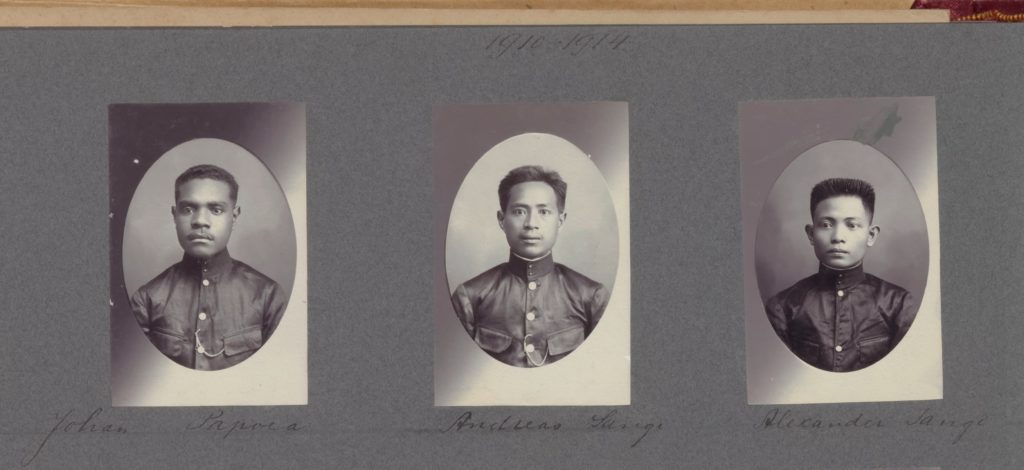

This next source is a photo of the eldest son of Jonathan Ariks, Johan, in the school album of the protestant seminary at Depok, Java. The boys are positioned next to each other with an indication of their ethnicity instead of their family name, so ‘Johan, Papoea’ next to ‘Andreas, Sangi[r islands].7

The subscript of the photo reads ‘Lamberthus Ariks’, which indicates that in all probability this is one of the sons of Jonathan Ariks. The Protestant missions in the Dutch Indies founded a joint seminary to educate young adults from local communities as missionary helpers and/or teachers at Depok, Java.8

The seminary was meant for indigenous children who were considered to be ‘promising’. They had often been educated at missionary schools, had been raised within missionary households as live-in pupils/servants (the ‘anak piara’ system) or, as was the case in Dutch New Guinea, had been raised as step-children bought from local situations of adoption, captivity or slavery. The archive contains information about its pupils in photographs, reports of the director about their behaviour at the seminary and brief indications of their further life course. These may involve judgements about their behaviour or school results. The archive also contains information about daily matters such as food. The archive, furthermore, contains information about the organisation, the board, the finances and some correspondence (possibly some about pupils).

Pupil’s voices or perspectives are mostly only present as second-hand reports or notes, although there are exceptions, such as letters about their further (successful) career after leaving school. Voices of resisting or ‘failing’ students can only be retrieved in descriptions of misbehaviour or protest, for which the students were reprimanded, punished or expelled. Despite these distortions, the archive offers a rare possibility to follow colonised missionary subjects individually.

Just as Benedict Anderson has noted for local administrators in the Dutch Indies, these young adolescents met members of very diverse ethnic/religious communities of the Dutch Indies Archipelago and thus learned to identify with this larger, Indonesian national community. At the Depok seminary, Christianity, of course, constituted the core binding element, but the fact that the adolescents came to know and ‘oversee’ the archipelago was of central importance to their awareness of both their own regional specificity and the national community. This also made this a place of possible nationalist activism. Concerning the children Johan and Lamberthus Ariks, it is possible they had a different experience, for Papuans were often looked down upon by other people from the archipelago because of their different physical appearance or so-called ‘race’. Christian belief may have functioned to bridge this gap, but this turned out not to be sufficient for Johan Ariks to embrace the incorporation of West Papua within Indonesian borders in the 1950s and 1960s.

Source 5: Studiefonds: Jonathan’s daughter Marietje and the Rumainum children

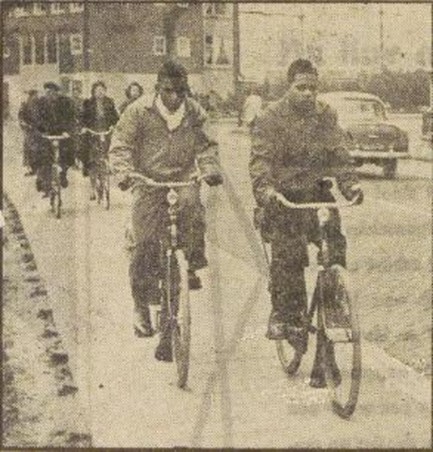

This newspaper photograph is a visual reference to the archive of the Studiefonds Nieuw Guinea.9

Studiefonds Nieuw-Guinea was a fund to support education and study in the Netherlands for promising young Papuans between 1956 and 1972. This was an initiative of the protestant mission supported by successful Papuan missionary teachers and helpers – among whom were the descendants of Marietje Ariks and Willem Rumainum, such as Reverend Felipe J.S. Rumainum. The idea behind the fund was clearly to educate promising young Christian Papuans – both men and women – in order for them to play a future key role in an independent West New Guinea. This did not happen, as New Guinea became a province of Indonesia in 1962.

The archive includes reports about their school or study results, letters to their ‘stepfather’ in the Netherlands, Reverend Slump, and reports about excursions and holidays in Europe. It also contains sources pertaining to the founding of a political group known as Kobe Oser on 19 December 1960, a group of young Papuans aiming at creating a feeling of common belonging between Papuans from different tribes. The archive does contain some of the correspondence of the former students, written from their diverse diasporic locations, with Reverend Slump after 1962.

Among the students was Jonathan and Paulina’s (great-)grandchild Fientje Ariks; records with regard to her stay in the Netherlands can be found among the sources. Other family names of Papuans who were politically active or active in the church also appear in this archive. The archive is accessible online after receiving permission from the Dutch Protestant Church (PKN) and under the strict legal restrictions with regard to privacy.

The Dutch National Archives also contain material concerning this fund and their students. For this archive you do not need special permission. It contains information about the individual students.10

Source 6: The political activities of Johan Ariks

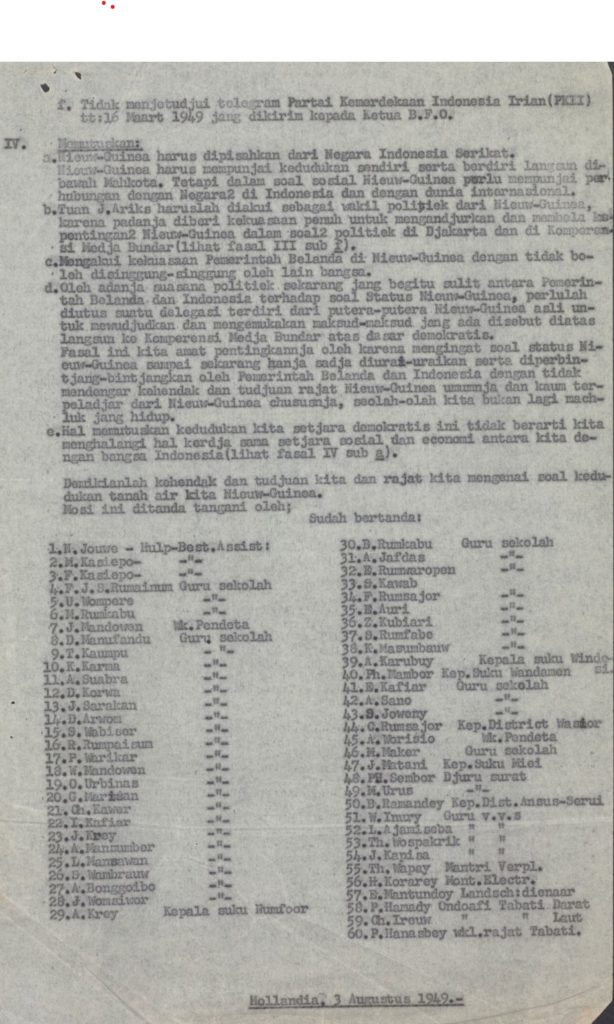

- The Dutch shorter version of the request, translated into English:

With a covering letter, dated Hollandia 5 August 1949 signed by Nicolaas Jouwe, was presented a motion, adopted on the same date by some 60 suku- and adat heads in Hollandia, Sermi, Blak, Supiori Nomfoer and Wendamen, to the effect

a. that Nieuw-Guinea should be placed outside the R.I.S. (Republik Indonesia Serikat, United States of Indonesia) and should obtain a separate status under direct connection with the Crown, which does not imply, however, that New Guinea does not need to cooperate with the R.I.S. in the furtherance of its social interests;

b. that Johan Ariks be regarded as the sole political representative for New Guinea, both at the relevant talks in Batavia and at the R.T.C (Round Table Conference);

c. that the Netherlands Authority is recognised as the sole legitimate authority for New Guinea;

d. that for the discussion of the New Guinea matters at the R.T.C. the country should be represented by a delegation from and by New Guinea (apart from b); that this point is considered to be of the utmost importance, since the procedure followed up till now has shown that the voice of the people of New Guinea has not been heard in this matter;

e. that the choice for this separate status is in no way intended to be an obstacle to social-economic cooperation with the Indonesian people.

In 1949, the future of the Republic of Indonesia and the status of Dutch New Guinea in relation to it was discussed on an international level at the Round Table Conference. Several Papuan intellectuals, mostly groomed and educated by the Protestant mission in Northern Dutch New Guinea (the area of Manokwari, Hollandia and the island Biak), organised political actions by sending requests to the Dutch government and her Majesty Queen Wilhelmina. The Dutch National Archives contain their requests (both in Malay and Dutch), the comments of the governor of New Guinea, Eechhoud, and further Papuan responses to the developments. Nicolaas Jouwe is the Papuan who organised these political actions. The requests are signed by individual Papuans with their names and an indication of their location and function. Johan Ariks is put forward by around 60 Papuan representatives of this region, each representing a kampong or church. The records show Ariks to be very sharp and critical. Ariks’ role is disputed by other Papuans – the archive contains some evidence of conflicts between certain groups. The archive does not contain much information of voices other than those that are described as ‘highly developed’ Papuans.

Much of the archive is in Malay. The documents the Dutch administration deemed most important and/or were presented to the minister and her Majesty were translated. The whole file of 156 pages has been digitised.

4. Provenance of the sources

All the archives and documents pertaining to the history of Jonathan Ariks, his son Johan and his daughter Marietje and their descendants stem from Dutch missionary or colonial archives located in the Netherlands, except for the oral information gained by anthropologist Jelle Miedema in the 1970s. The latter’s description of the place of children and the practice of the adoption and selling of children among local tribes in the Bird’s Head mountain and plains area, are helpful for understanding how a child became available for ‘purchase’ by the missionaries.

The missionary archives (letters and diaries) give fragmentary evidence of these purchased children. In their journals, stories of children were clearly framed to move the Christian readers, by both stressing the misery the children came from and the successes of the mission in terms of education, behaviour and belief. In this discourse, a pious deathbed was considered a triumph. The perspective of the children, their voices and their experiences can hardly be retrieved at all, unless they totally align with what the missionaries wanted to hear. Only some diaries and letters reveal more resistance, dispute and problems which may indicate other perspectives. With difficulty, fragments about these children’s lives can be stitched together to get an idea of an individual life course (over generations), mostly only for children who did well in the missionaries’ eyes.

The archives of the Depok Protestant missionary seminary and of the Studiefonds Nieuw Guinea show the Dutch belief in education as a way of emancipating Papuan people along a strictly defined Dutch colonial model of (Christian) development. Jonathan and Johan Ariks were considered outstanding examples of this model. This put Jonathan Ariks in the position of a missionary helper, and Johan Ariks in a position of guru and – after having been a prisoner of the Japanese during the Japanese occupation – the designated leader of Papuan nationalist politics. These nationalist politics were not directed against the Dutch coloniser, but against the usurpation of West New Guinea by the United States of Indonesia in 1949. These archives are strongly framed within this discourse of ‘developing’ the ‘primitive, heathen’ people of New Guinea towards ‘autonomy’, guided by the Dutch. The voices of Papuans who were not so much under missionary control and not educated according to Western principles, can hardly be heard.

5. Postcolonial continuities

The Papuan children who had been bought and were successfully raised and educated by missionaries of the Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging constituted the roots of a widespread Christianisation of the region around Hollandia and Manokwari in the twentieth century. After the Second World War, these gurus, teachers and their descendants articulated Papuan nationalist aspirations. While the Dutch had hoped to be able to show off their good colonial intentions and ‘development’ work, for these educated Papuan people their education provided the opportunity to speak up as autonomous (post)colonial subjects against Indonesia. As the Dutch could not back up or ‘supervise’ these aspirations anymore after Indonesia took over the rule over New Guinea in 1962, Papuan politicians raised under Dutch tutelage were left to their own fate. Many of them fled to the Netherlands, others migrated to Australia. Until this day, tensions between Papuan nationalists and Indonesia and Indonesians lead to violent confrontations.

6. Unanswered questions and silences

Why were children presented to the missionaries as ‘for sale’? How had they become captured or ‘enslaved’? We only have a careful historical-anthropological reconstruction of the possible reasons, but we don’t have first-hand stories from the peoples the children came from. The story of Jonathan Ariks is the only exception.

We do not know how many children were ‘redeemed’ by the missionaries in total; we estimate an amount of 100-300 children. How many of them returned to their own communities, how many died, how many became successful gurus or helpers for the mission, we do not know.

It is not exactly clear whether, between 1906 (when the Van Hasselt couple left) and 1940, other ways of ‘adopting’ Papuan children were developed; during this period, there was much more colonial intervention in local systems of slavery.

After having been groomed and educated as Christian Papuans, it was almost impossible to return and become part of one’s community again. Not only were the children considered slaves and the possession of the missionaries, they lacked the necessary gift-kin network needed within such communities. How, then, did these ‘educated’ or ‘elite’ Christian Papuans later return as gurus to Papuan communities? How did these re-connections happen?

7. Collaboration and conversation: call for input

As a historian who is critically engaging with this missionary colonial history, I am interested in the perspective and voices of the descendants of children who were once ‘redeemed’ by the missionaries. This pertains to those who stayed in West Papua after Indonesia took over the power, as well as to the diaspora in the Netherlands and in for example Australia.

Are you a descendant of a child once ‘redeemded’ from slavery by the mission? Could you tell us more about their and your own history in relation to that period?

Do you know of gurus or kampong heads who were descendants of such children?

Do you know of Papuans who studied in Depok, Java, at the missionaries’ seminary? Or of their family or descendants?

Do you know Papuans who studied in the Netherlands between 1956 and 1962? Or of their family or descendants?

8. Life stories linked to this child

9. Further reading

- Jan. S. Aritonang and Karel A. Steenbrink. A History of Christianity in Indonesia. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2008.

- P.J. Drooglever. Een daad van vrije keuze: De Papoea’s van westelijk Nieuw-Guinea en de grenzen van het zelfbeschikkingsrecht. Amsterdam: Boom, 2005.

The most extensive work on the history of the Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging comes from Freerk Kamma, a missionary and anthropologist in the 1950s:

- Freerk Christiaans Kamma. ‘Dit wonderlijke werk’: Het probleem van de communicatie tussen Oost en West gebaseerd op de ervaringen in het zendingswerk op Nieuw-Guinea (Irian Jaya), 1855-1972 ; een socio-missiologische benadering. Oegstgeest: Raad voor de zending der Ned. Hervormde Kerk, 1977. Digital version via Google: https://books.google.nl/books?id=eZYEAQAAIAAJ&q=freerk+kamma&dq=freerk+kamma&hl=nl&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjLgqLPzrLwAhWDsaQKHaN4DOEQ6AEwCXoECAgQAg.

A historical-anthropological reconstruction of the reason that children were sold to the missionaries:

- Geertje Mak. ‘Children on the Fault Lines: A Historical-Anthropological Reconstruction of the Background of Children Purchased by Dutch Missionaries between 1863 and 1898 in Dutch New Guinea’. BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 135, nos. 3-4 (2020): pp. 29-55. https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.10876.

Contemporary anthropological analysis of the Papuan region where Dutch Protestant missionaries were active, in particular Biak. Includes historical analysis and analysis of Papuan nationalism:

- Danilyn Rutherford. ‘Frontiers of the Lingua Franca: Ideologies of the Linguistic Contact Zone in Dutch New Guinea’. Ethnos 70, no. 3 (2005): pp. 387-412.

- ———. Laughing at Leviathan: Sovereignty and Audience in West Papua. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- ———. ‘Love, Violence, and Foreign Wealth: Kinship and History in Biak, Irian Jaya’. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Incorporating Man Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4, no. 2 (1998): pp. 255-82.

Dutch anthropological studies of the Bird’s Head mountains and plains region, including historical overviews:

- Jelle Miedema. ‘Anthropology, Demography and History; Shortage of Women, Inter-Tribal Marriage Relations, and Slave Trading in the Bird’s Head of New Guinea’. BKI Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 144, no. 4 (1988): pp. 494–509.

- ———. De Kebar, 1855-1980: Sociale structuur en religie in de Vogelkop van West-Nieuw-Guinea. Dordrecht: Foris, 1984. For PDF see: https://papuaerfgoed.org/nl/BK/40/377.

Three recent studies of Dutch Catholic missions active in southern Dutch New Guinea, using very similar practices in which the grooming and education of children was central:

- Maaike Derksen. ‘Local Intermediaries: The Missionising and Governing of Colonial Subjects in South Dutch New Guinea, 1920-1942’. Journal of Pacific History 51, no. 2 (2016): pp. 111-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2016.1195075.

- ———. ‘“Removing the Youth from their Pernicious Environment”: Child Separation Practices in South Dutch New Guinea, 1902-1921’. BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 135, nos. 3-4 (2020): pp. 56-79. https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.10874.

- Marleen Reichgelt. ‘Children as Protagonists in Colonial History: Watching Missionary Photography’. BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 135, nos. 3-4 (2020): pp. 80-105. https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.10869.

10. Author

Geertje Mak is currently working on a project on the early missionary history of Dutch New Guinea (1862-1906) in which the purchased children are put centre stage. She is a professor of Gender History at the University of Amsterdam and senior researcher at the NL-Lab of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Contact: geertje.mak@huc.knaw.nl

Notes

- F.C. Kamma, ‘Dit Wonderlijke Werk’.[↩]

- Het Utrechts Archief, the Netherlands, Archief van de Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging (UZV), 1859-1951 https://hetutrechtsarchief.nl/collectie/609C5B9FB6A04642E0534701000A17FD.[↩]

- See for a detailed overview of the (history of) the archive in Dutch: https://hetutrechtsarchief.nl/onderzoek/resultaten/archieven?mizig=210&miadt=39&miaet=1&micode=1102-1&minr=2970613&miview=inv2#inv3t2.[↩]

- Jelle Miedema, De Kebar, 1855-1980: Sociale structuur en religie in de Vogelkop van West-Nieuw-Guinea (Dordrecht: Foris, 1984), pp. 38-39, see also pp. 238-240. This PhD thesis is available online at: https://papuaerfgoed.org/nl/BK/40/377.[↩]

- Jelle Miedema, De Kebar, 1855-1980: Sociale structuur en religie in de Vogelkop van West-Nieuw-Guinea (Dordrecht: Foris, 1984), pp. 238-240.[↩]

- Utrechtse Zendingsvereeniging, Berigten van de Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging (Utrecht: Kemink & Zoon, 1860-1917), cit. 1892, p. 38. Digitally available via Delpher (Dutch database for historical newspapers and magazines).[↩]

- Het Utrechts Archief, the Netherlands; Archief van de Raad voor de Zending, 1102-1, Archief van het Comité Depok, file number 2668, Stamboek van kwekelingen van het Seminarie van Depok, 1878-1924. The material has not yet been digitised. Inventory: https://hetutrechtsarchief.nl/collectie/609C5B9FE3394642E0534701000A17FD.[↩]

- An introduction (‘Inleiding’) to the archive of this seminary and an inventory in Dutch is available at: https://hetutrechtsarchief.nl/collectie/609C5B9FE32A4642E0534701000A17FD.[↩]

- Studiefonds Nieuw-Guinea, Utrechts Archief, Raad voor de Zending 1102-2, nos. 672, 3199, 4426, 4487-4492, 4499-4504, 4508, 5728.[↩]

- See: Nationaal Archief, 2.10.54, Archief van het Ministerie van Koloniën en opvolgers: Dossierarchief 1945-1963, file numbers 6237-6241.[↩]

- Nationaal Archief, the Netherlands, The Hague, 2.10.14 Inventaris van het archief van de Algemene Secretarie van de Nederlands-Indische Regering en de daarbij Gedeponeerde archieven, (1922) 1944-1950, file number 2512: 2512 Ingekomen rekesten van autochtone groeperingen betreffende de status van Nieuw-Guinea en stukken betreffende de akties van J. Ariks, politiek vertegenwoordiger van Nieuw-Guinea in Batavia. This specific page: https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/onderzoeken/archief/2.10.14/invnr/2512/file/NL-HaNA_2.10.14_2512_0022?tab=metadata.[↩]

Jonathan Ariks born

Jonathan Arkis is ransomed