Elisabeth Fatuma an African girl purchased and brought to Germany

1. Abstract

Fatuma – sometimes spelled Fathuma – was born in the late 1880s in what is present-day Tanzania. She was taken to Bethel, Germany in 1891. Unfortunately, the archival sources do not start until Fatuma was no longer in the care of her parents, which means that the earliest memories of her have disappeared. The sources that are available are biased, as they were written from the perspective of German missionaries.

2. Timeline

3. Elisabeth Fatuma’s story

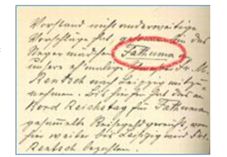

The first mention of Elisabeth Fatuma is found in a letter written by Jacob Greiner, who worked as missionary of the Evangelische Missionsgesellschaft für Deutsch-Ostafrika (Protestant Missionary Society for German East Africa, EMDOA) in German East Africa.

Missionary Greiner was the first missionary of the EMDOA to be sent to Dar es Salaam in 1887. He reportedly met Elisabeth as he was travelling back to Germany on home leave. In a letter to Friedrich von Bodelschwingh, an influential board member of the EMDOA, Greiner first reported that he had ransomed Fatuma in June 1891 during a holiday to Germany and wanted to give her into the care of the missionary sister Frau Rentsch in Leipzig. However, this did not happen, for unexplained reasons about which the few available sources unfortunately do not give us any information. According to contemporary publications, Greiner met a couple on a ship (the husband was an African soldier in the service of the German Schutztruppe) who wanted to sell Fatuma, who was about five years old, into Egyptian slavery for 800 francs. Another child, a boy named Ali who was estimated to be thirteen years old, was reportedly also ‘freed’ from the hands of slave traders by English troops at the same time.1

To understand the background of what Greiner and the EMDOA were doing in East Africa, a short digression into German colonial history is necessary:

With the unification of Germany and the founding of the so-called Second German Empire in 1871, the desire for German colonies grew. After the ‘Berlin Africa Conference’ in 1884/1885 tried to clarify the relationship between the European colonial powers, the colony of German East Africa was established. The DOAG (‘Deutsch-Ostafrikanische Gesellschaft’) tried to win political favour by helping to stop the slave trade. Furthermore, it planned to arouse the interest of missionary societies for the area of East Africa, in order to help ‘civilise’ locals and make them ‘useful’ for the colonial project. Since none of the established missionary societies were willing to commit to East Africa, various members of the DOAG founded the EMDOA, so that in the first years of the constitutional phase the two societies were partly intertwined in terms of personnel and partly also in terms of organisation. The EMDOA was finally founded in Berlin on 12 April 1886. Its intended task was the ‘Heidenmission’ (‘heathen mission’) and pastoral care for Germans. Until about 1890, there was always controversy on the board and in the circle of supporters of the EMDOA, until Friedrich von Bodelschwingh was appointed to the board directed the organisation, making the so-called ‘Äußere Mission’ (‘Outer Mission’) important for the Bethel community as well.2

Ali was baptised and named Johannes in 1893. He died a few months later of consumption (probably tuberculosis), as did Fatuma in 1895.

The EMDOA began its work on the coast of what is now Tanzania, in Dar es Salaam and its surrounding areas, in 1890. In order to be able to work in the Usambara Mountains, the EMDOA officially renounced the protection of the German Empire through the two missionaries Ernst Johanssen and Paul Wohlrab. Successively, more missionaries joined and the number of EMDOA stations increased until the First World War, when German missionaries were forced to leave German East Africa.

Source 2: Elisabeth Fatuma and Sister Lina Diekmann in Bethel

On 3 June 1891, Fatuma and Ali were finally brought to Bethel by Greiner. Ali lived in a home for boys. In 1893, he was baptised and named Johannes. He died a few months later, in April 1893, of consumption (probably tuberculosis). Fatuma was admitted to a children’s home of the deaconesses’ institution Sarepta, run by Sister Lina Diekmann and others. In the opinion of the EMDOA, Fatuma had to be shaped into a pious Christian, so that she would be able to return to East Africa to spread the Gospel and to be a positive example for the work of the mission one day.

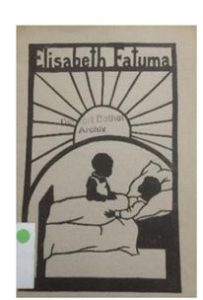

Source 3: Friedrich von Bodelschwingh, Elisabeth Fatuma (Bethel, 1895/1896).

Elisabeth Fatuma written by Friedrich von Bodelschwignh in 1895/1896

In the pubication Elisabeth Fatuma, written by Friedrich von Bodelschwignh, the head of the EMDOA at this time3 describes the development of Fatuma in the children’s home in Bethel. It further reports that Fatuma made ‘progress’ in the supposed Christian sense. In this respect, he describes her appearance, her clothing, her language and her behaviour, which was now only very rarely characterised as ‘wild’.

The book further details how Fatuma made friends after alleged difficulties in adapting to her new environment and how she developed positively in a contemporary Christian sense and, for example, quickly learned German and became more and more interested in the stories about Jesus and passed them on to the other children. According to Friedrich von Bodelschwingh, her mood also changed to a much calmer, more balanced one, so that Fatuma was allowed to take care of the babies in the children‘s home soon. Furthermore her willingness to help and to serve/to work increased, as von Bodelschwingh stated in his paper. He described her ‘progress’ as ‘extremely rapid’ in the contemporary Eurocentric sense. He mentioned how enthusiastically Fatuma took part in the baptism class and also noted her anticipation of her baptism, after which, according to von Bodelschwingh, her behaviour was even more pious than before, as she started acting as intended role model for the other children by telling them biblical stories. In 1891, at Christmas, Fatuma was baptised as Elisabeth at Zion Church.

By 1895, Elisabeth Fatuma was ill and dying. Her death was described as a patient suffering, normalising Christian expectations of child death of the period.

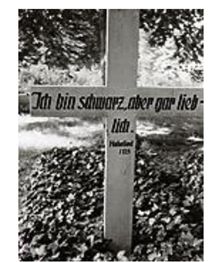

Source 4: Elisabeth Fatuma’s grave

Elisabeth Fatuma was buried at the Zionsfriedhof in Bethel. A cross marks her grave. The translation of the German inscription reads:

Elisabeth Fatuma, born in Africa, died in Kinderheim on 26 March 1895. I am black, but comely.4

The verse ‘I am black, but comely’ is taken from the Old Testament book Song of Solomon 1:5. This text was later changed to another Chiristian text, ‘Here rests in God’, that focused on the inner transformation of Elisabeth Fatuma to Christianity, rather on her outer appearance. When and why this change ocurred remains to be uncovered.

4. Provenance of the sources

Many of the sources used here are from the Archives and Museum Foundation of the United Evangelical Mission, held in Wuppertal, Germany. These archives can be accessed by the public and include detailed finding aids avaliable online. More sources may be available in the Hauptarchiv Bethel.

5. Postcolonial (dis)continuities

Today, the alliance ‘Decolonize Bielefeld’ is campaigning for the renaming of Karl-Peters-Straße to Fatuma-Elisabeth-Straße. (www.decolonize-bielefeld.de)

6. Silences

There are many silences surrounding Elisabeth Fatuma’s life. No detailed knowledge is available as to the family she was separated from in Africa, where exactly she came from, or why the separation occurred. There is little information as to date as to how common the practice was of separating children and sending them to German children’s homes. We do not know how many children’s homes such as Bethel took on African children that had been purchased in the colonies.

7. Collaboration and converstion: call for input

We are looking to find more sources and voices that might help shed light on Elisabeth Fatuma’s life in Germany and her origins.

8. Links to other vignettes

9. Further reading

- Gustav Menzel. Die Bethel-Mission: Aus 100 Jahren Missionsgeschichte. Wuppertal: Verlag Vereinte Ev. Mission, 1986.

In German, more information on the Bethel Mission.

- William Clarence-Smith. ‘The Redemption of Child Slaves by Christian Missionaries in Central Africa, 1878-1914’, in Child Slaves in the Modern World, edited by Gwyn Campbell, Suzanne Miers and Joseph C. Miller, pp. 173-190. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2011.

10. Authors

Notes

- Elisabeth Fatuma, written by Friedrich von Bodelschwingh. See also: Wolfgang Apelt, Short History of the United Evangelical Mission (Wuppertal: Archiv- und Museumsstiftung der Vereinten Evangelischen Mission, 2008).[↩]

- In July 1906, the EMDOA moved to Bethel.[↩]

- He is also the namesake of the von Bodelschwinghschen Stiftungen – which is today a diaconal and social business in Bielefeld.[↩]

- ‘Elisabeth Fatuma, geboren in Afrika, gestorben im Kinderheim am 26. März 1895’. The verse is taken from the Old Testament book Song of Solomon: ‘Ich bin Schwarz, aber gar lieblich’.[↩]

Elisabeth Fatuma born

Elisabeth Fatuma ransomed

Elisabeth Fatuma dies in Germany