Raden Roro Moerjan one of the first students at an elite girls’ boarding school in Yogyakarta in the 1910s

1. Abstract

Raden Roro Moerjan was around twelve years old when her parents registered her at the Koningin Wilhelmina School (Queen Wilhelmina School, KWS) in Yogyakarta in 1907. The KWS was a Dutch-language Protestant school that had been established at the initiative of the Dutch Reformed mission in collaboration with a group of philanthropic elite women in Amsterdam. The school aimed to offer Christian education to the daughters of priyayi families, the Javanese nobility. In their boarding school, the KWS teachers consciously created physical, emotional and cultural distance between the students and their Javanese home environment. Moerjan remained in touch with the school and its teachers until she passed away in 1916, at the age of twenty-one.

2. Timeline

3. Raden Roro Moerjan’s Story

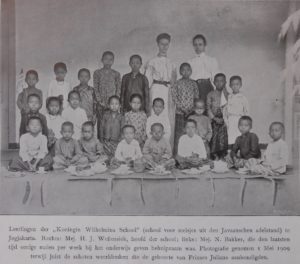

Transcription: Leeringen der ‘Koningin Wilhelmina School‘ (school voor meisjes uit den Javaanschen adelstand) te Jogjakarta. Rechts: Mej. H.J. Wellensiek, hoofd der school; links: Mej. N. Bakker, die den laatsten tijd eenige malen per week bij het onderwijs geven behulpzaam was. Photographie genomen 1 Mei 1909 terwijl juist de schoten weerklonken die de geboorte van Prinses Juliana aankondigden 1.

Translation: Students at the ‘Koningin Wilhelmina School’ (school for Javanese girls from the noble classes) in Jogjakarta. Right: Miss H.J. Wellensiek, head of the school; left: Miss. N. Bakker, who recently assisted with the teaching a few times a week. Photograph taken May 1, 1909, just as the shots were ringing out announcing the birth of Princess Juliana.

This group picture of the students and teachers at the Koningin Wilhelmina School (KWS) in Yogyakarta. was taken at the birth of the Dutch heir to the throne Princess Juliana in 1909. Several children are holding Dutch flags at this occasion, that was extensively celebrated by the Dutch community in the Dutch East Indies. From other sources in the KWS-archive, we can derive that the name of the tallest girl in the picture, fourth from the left at the top row, was Raden Roro Moerjan. Raden Roro was the title that she carried as an unmarried female member of the priyayi, the Javanese nobility, and Moerjan was her given name.

The picture was published in in the second yearly report of the school, that was opened in 1907 at the initiative of the Dutch Reformed mission. This school was funded partly through the fundraising efforts of a committee of upper-class Protestant women in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The KWS was a Protestant school for girls who belonged to priyayi families, nobles of the robe who had family connections to one of the princely houses in Yogyakarta. It was located in the Bintaran neighbourhood in the inner city of Yogyakarta, close to the residences of the Sultan and the local ruler Paku Alam. The Dutch-language curriculum focused on reading, writing, Christian religious education, and domestic skills.

The Dutch Protestant initiators aimed to attract girls from the highest noble families, hoping that Christian education for elite girls would eventually lead to the religious conversion of the Muslim upper classes. They did so by consciously creating distance between the students in their boarding school and their Javanese home environment. According to Protestant missionaries, the priyayi were hard to reach for the mission as they did not make use of missionary services such as the Petronella hospital, that had opened in the city in 1900. Johanna Kuyper, a former nurse at the hospital and a daughter of the Calvinist politician Abraham Kuyper, coordinated the establishment of the support committee in Amsterdam.

While the KWS was intended as a girls-only school, the headmistress H.J. Wellensiek initially had difficulty attracting female students. Priyayi families preferred to enroll their sons and were reluctant to pay the high school fees for the education of their daughters. A Dutch-language education was advantageous for priyayi boys, as it was an asset for jobs in the civil administration, a field in which many priyayi men worked. Therefore, the school was forced to admit young boys in the first years of its existence to ensure financial stability. Boys could only be enrolled if their sisters went to the school as well. In the image above, we see that there are more male than female students.

Source 2: Notes of KWS headmistress H.J. Wellensiek to the Support Committee in Amsterdam

Source: Atria IAV SCHIM inv. no. 40, letter H.J. Wellensiek to the Ladies’ Committee in Amsterdam, undated.

Transcription: Moerjan, dochter van den djaksa, zusje van Soedar. Na Moertinah’s vertrek is zij de oudste leerling, maar ik heb aan haar lang zooveel niet als aan hare zuster. Zij is zeer moeilijk te begrijpen en daardoor ook moeilijk te behandelen: een kind (± 14 jaar), dat het eene oogenblik alles vergeet en staan laat, om te knikkeren en het volgende oogenblik vragen doet, die getuigen van groote belangstelling in Gods Woord en goed nadenken boven haar leeftijd. Zij is de eenige, die eens beslist geweigerd heeft, te doen, wat ik zei, open in eene volle klasse; maar ook ontving ik eens aan tafel eene lei van haar: ‘Juffrouw, ik heb vanmorgen gejokt, maar gebid ook.’ Daarbij pleitte ook voor haar, dat zij niet zelf de lei bracht, maar een kind stuurde, dat niet lezen kon. Ik heb nooit met haar over deze zaak verder gesproken, maar na dien tijd ook nog een leugen gemerkt. N.B. Dit overslaan!

Translation: Moerjan, daughter of the jaksa, sister of Soedar. After Moertinah’s departure she is the oldest pupil, but she is of much less use to me than her sister. She is very difficult to understand and therefore difficult to handle: a child (± 14 years), who one moment forgets everything around her, puts down whatever she is doing and leaves to go play with marbles, and the next moment asks questions that testify to a remarkable interest in the Word of God and a sharp mind for her age. She is the only one who once adamantly refused to do what I said, openly in a full classroom; but once I received a slate from her at the table: ‘Miss, I told a lie this morning, but I prayed as well.’ It was also to her credit that she did not bring the slate herself but sent a child who could not read. I never spoke to her about the matter anymore, but after that I also noticed a lie. N.B. Skip this!

Description:

This is a fragment from a long letter that headmistress Wellensiek wrote to the support committee in Amsterdam, presumably in 1909. In the letter, Wellensiek described the picture mentioned above and wrote a brief report on each of the students featured in the photograph. She reported on their character, their behaviour in class, and in some cases on their family background. From the letter, it is possible to gauge some more information about Moerjan. Wellensiek writes that she is about fourteen years old, and that she is the sister of Soedar, who is pictured in the front row, the sixth child sitting on the floor from the left. Their older sister Moertinah, who had been the oldest girl at the school for a time, had already left the KWS by the time Wellensiek wrote this letter.

The siblings were the children of a jaksa, a prosecutor in the Javanese legal system, and the family lived in the kraton, the Sultan’s residence. While the KWS tried to attract children from the family of the Sultan, because they believed these would be most influential in converting upper-class Javanese, in practice the school attracted mainly children from mid-ranking priyayi families who aspired for a career in the colonial service. We do not know why the parents of Moertinah, Moerjan and Soedar decided to send their children to the school, but the teachers often noted that priyayi families insisted that their children learn Dutch in the briefest possible time. Knowledge of Dutch markedly improved the marriage chances of a girl in a time when priyayi elites sought proximity to the Dutch colonial regime.

According to this letter, their parents told Wellensiek that their son Soedar was four years old, but according to her he was much older: boys were only allowed at the school under the age of seven. It is possible that the parents wanted to register their son and enrolled their two daughters because boys were not admitted unless their female siblings came to school as well.

In the letter, Wellensiek criticised Moerjan’s character and compared her unfavourably to her sister Moertinah who, as can be read in other sources, often helped the teachers by instructing the younger children. Nevertheless, Wellensiek also mentioned that Moerjan’s character was ‘improving’, and that she showed an interest in the Gospel. Missionaries often described Javanese people as dishonest, and claimed Christian education had a positive effect on indigenous children’s characters. Wellensiek also described an instance in which Moerjan had disobeyed her and marked this with a note for the support committee, possibly to ensure that this would not end up in one of the yearly reports that the committee sent to its audience in the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies. Eventually, the letter was not mentioned in any material published by the committee.

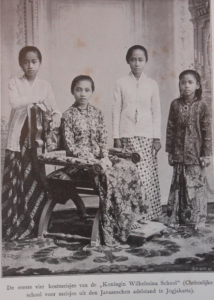

Source 3: A picture of the first four boarding girls at the KWS, 1910.

Source: AtriaIAV SCHIM inv. no. 7, ‘Derde Verslag van het Comité van Bijstand voor de “Koningin-Wilhelmina-School”, Christelijke School voor Meisjes uit den Javaanschen Adelstand te Jogjakarta, van 1 Juli 1909-30 Juni 1911’.

Transcription: The four first boarding girls of the ‘Queen Wilhelmina School’ (Christian school for girls from the Javanese noble classes in Jogjakarta).

Description: In the second picture we encounter Moerjan again, this time sitting on a chair surrounded by three fellow students of the KWS. The picture was published in 1910 in the third yearly report of the school. Moerjan had entered the boarding school as its very first student in November 1909. According to the teachers, her parents now considered her too old to be seen in public on her way to school every day. This aligns with priyayi customs surrounding girlhood: when priyayi girls reached the marriageable age, around the time of their first menstruation, they were traditionally secluded at home in preparation of an arranged marriage. If a marriageable girl was seen in public, this could potentially compromise her respectability and diminish her marriage chances. This custom, called pingit, was movingly described by the well-known author Raden Ajeng Kartini, who was taken out of school at the age of twelve to enter seclusion. Wellensiek also mentioned that Moerjan was not allowed to go out beyond the garden of the boarding school.

The picture portrays the first four boarding school students in a solemn environment, dressed in richly decorated batik sarongs and kebayas. Moerjan is wearing the same kebaya as in the first picture and her feet are resting on a low footstool, as was common in portraits of priyayi women. From other sources, we know that two of the other girls were sisters, one of whom was named Totik. The youngest girl was named Siti and was from Demak, a city in the north of Central Java. The picture was taken in photo studio Schnabel, most likely at the initiative of headmistress Wellensiek. It was sent to the support committee in Amsterdam, which printed the picture in its yearly report to celebrate the entrance of the first boarding girls in the school.

Source 4: Moerjan’s letter to Henriëtte Kuyper

Source: Atria IAV SCHIM inv. no. 41, letter from Moerjan to Henriëtte Kuyper, 22 December 1911.

Transcription:

Bandoeng, 22 december 1911

Lieve Juffrouw Kuyper!

Beleefd dank ik U, voor Uwen lieven brief. Ik kan U niet zeggen, hoe blij ik er mee ben.

Ach, ik wou maar, dat ik U iets van de Koningin Wilhelminaschool kon vertellen. Maar helaas, ik kan dat niet meer doen, want zooals U weet, ben ik niet meer op Binataran. Ja Juffrouw, U hebt ’t goed geraden, ik hou ook werkelijk veel van die school, en ook van Juffrouw Wellensiek. Ach ik vind ’t toch erg jammer, dat ik nu meer op Bintaran ben. Maar ’t kan niet anders, want mijn Ouders willen ’t zo hebben. Ze zeggen, dat ik nu veel te groot ben, om naar school te gaan. En dus zit ik nu in Bandoeng, met mijn Moeder, mijn Broer en mijn kleine Zusje. Want ziet U, mijn Broer is hier Dokter.’

U schreef in Uw brief, dat, waar ik heen ga, de Heere met mij gaat, en dat Hij overal is, en in liefde neder ziet op degene, die Hem lief hebben.

Ja Juffrouw, ’t is zoo. U hebt goed gezegd. Ik geloof ook, dat de Heere mij dag en nacht bewaakt, en mij als een Vader, ja eigenlijk nog méér dan een Vader verzorgt.

Nu zal ik u iets van Uw Zuster Juffrouw Kuijper vertellen. Ach, wij vinden het zoo jammer, dat uw Zuster naar Holland gaat, want wij houden allemaal van de Juffrouw. Juffrouw Kuijper bedenkt altijd iets, om ons plezier te doen. Uw Zuster is goed voor iedereen.

En nu gaat die goede Juffrouw van ons weg. Ach, ach, wat jammer!! Maar uw Vader heeft haar immers geroepen? Nu, dan kan ze natuurlijk niet neen zeggen. En uw Zuster schreef mij, dat ze in Januari te Bandoeng komt. En dan kan ik haar zien. Heerlijk! Verrukkelijk!

Translation:

Bandung, 22 December 1911

Dear Miss Kuyper!

I thank you politely for your dear letter. I cannot tell you, how happy it makes me.

Ah, I wish I could tell you something about the Koningin Wilhelmina School. But unfortunately, I cannot do that anymore, because as you know, I am no longer at Binataran. Yes Miss, you guessed right, I really love that school, and Miss Wellensiek as well. But I am still very sorry that I am no longer at Bintaran. But I have no choice because my parents want it that way. They say I am much too big to go to school now. And so now I am in Bandung with my Mother, my Brother, and my little Sister. Because my brother is a Doctor here, you see.

In your letter, you wrote that the Lord comes along with me, wherever I go, and that He is everywhere, and He is lovingly looking down on those who love Him.

Yes Miss, that is right. You have said it well. I also believe that the Lord watches over me day and night, and cares for me like a Father, yes, even more than a Father.

Now I will tell you something about your Sister Miss Kuijper. Oh, we are so sad, that your Sister is going to Holland, because we all love Miss. Miss Kuijper always thinks of something, to make sure we have fun. Your Sister is kind to everyone. And now this good lady is leaving us. Oh, oh, what a pity!! But your Father has called her, has he not? Well, then, of course, she cannot say no. And your Sister wrote to me, that she will come to Bandoeng in January. And then I can see her. Wonderful! Delightful!’

Description: Moerjan wrote this letter to Henriëtte Kuyper, who was the chairwoman of the KWS support committee in the Netherlands, in late 1911, when she was about sixteen years old. Henriëtte Kuyper lived in The Hague.

In the letter, that was written from the city of Bandung, Moerjan expressed her disappointment about her departure from the Koningin Wilhelmina School. It is unclear when Moerjan left the school, but it must have been sometime between late 1909 and later 1911. She explains that her parents took her out of school because they now considered her too old to follow an education. She was most probably supposed to prepare herself for marriage and retire from public life, as was common for marriageable priyayi girls.

Moerjan went to live with her mother and two of her siblings in Bandung, where her brother was a doctor. Likely he was a graduate of the School tot Opleiding van Inlandsche Artsen (STOVIA, School for the Education of Native Doctors) that provided medical education to Indonesians. Many male members of middle- and lower-ranking priyayi families pursued medical careers. Because Moerjan gave the address of her father at the bottom of the letter, we know that her father Mangkoeredjo held the position of a jaksa in the village of Wonosari in the regency of Gunung Kidul, close to Yogyakarta.

Moerjan also wrote about the departure of Johanna Kuyper, the sister of Henriëtte Kuyper, who had apparently visited Yogyakarta or was perhaps still working in the city as a nurse at the Petronella Hospital. According to Moerjan, Johanna Kuyper had to return to the Netherlands at the insistence of her father, the influential Calvinist politician Abraham Kuyper. It is likely that Moerjan sent the letter to the KWS and that Johanna gave it to her sister when she was back in The Hague. Henriëtte had been instrumental for the fundraising for the school but had never visited the Dutch East Indies. Moerjan had thus never met her and perhaps wrote the letter after being encouraged to do so by her former teachers at the school.

In her letter, Moerjan briefly reflected on her relationship to Christianity, mentioning that she believed that God was watching over her. Of course, it is possible that Moerjan mentioned this because she understood that this would please Kuyper. While the initiators of the school had hoped to convert many girls to Christianity, priyayi families were generally not interested in this, and the number of conversions at the school remained low until the KWS school was converted into a coeducational primary school in the early 1930s. Yet, several former students wrote about their Christian beliefs in letters to their former teachers. At the KWS, students learned extensively about the Protestant faith and joined their teachers on church visits. It is unlikely that Moerjan had officially converted, as the support committee did not report on baptisms of students before the 1920s. From other letters in the KWS archive, we know that girls often encountered strong resistance from their families if they decided to get baptised.

Source 5: The report of Moerjan’s death, 1916

Source: Atria IAV SCHIM inv. no. 9, ‘Vijfde Verslag van het Comité van Bijstand voor de “Koningin-Wilhelmina-School”, Christelijke School voor Meisjes uit den Javaanschen Adelstand te Jogjakarta, van 30 November 1913 – 30 Mei 1917’.

Transcription: Dat Moerjan van ons is heengegaan, weet u zeker al. Ik heb haar maar een half jaar gekend, maar toch lang genoeg om te weten, hoeveel we aan haar verloren hebben. Wat hielden we allen van Moerjan, en hoe groot was haar invloed op de kinderen. Haar ligstoel, later haar bed, waren vaak het middelpunt van de aardigste toneeltjes. We weten, dat haar het sterven gewin was, dat al die jaren onder de beademing van het Evangelie voor haar niet zonder gewin zijn gebleven en dat zij in vrede is heengegaan. Dat is ons een groote troost, al valt dit verlies zwaar, vooral bij Juffrouw Wellensiek, bij wie Moerjan negen jaar gewoond is, en die in haar een zusje zag.

Translation: You surely already know that Moerjan has passed away from us. I have only known her for six months, but still long enough to know how much big the loss is. How we all loved Moerjan, and how great was her influence on the children. Her lounger, and later her bed, were often the centre of the most amusing little plays. We know that her death was a gain for her, that all those years under the breath of the Gospel have not been without gain for her, and that she has passed away in peace. That is a great comfort to us, although this loss is difficult, especially for Miss Wellensiek, with whom Moerjan lived for nine years, and who saw her as a little sister.

Description: In this fragment, that was published in the yearly report of the KWS in 1917, the teacher A. Jonkhoff described that Moerjan passed away in 1916, at the age of about 21. This was most likely a fragment from a letter that the teacher sent from Yogyakarta to the Amsterdam support committee. Moerjan apparently died after she had been ill and bedridden for a while. From this fragment it appears that Moerjan had returned to the KWS after her stay in Bandung, but it is unclear when and under which circumstances this happened. It was highly unusual for priyayi girls to still be unmarried at the age of 21, and perhaps this had something to do with Moerjan’s declining health. From Jonkhoff’s final remark, which refers to Moerjan’s ‘nine years’ spent at the school, we can perhaps conclude that the stay in Bandung had been brief. She also reports that the teachers were very sad at Moerjan’s passing, especially headmistress Wellensiek, who said she felt emotionally close to Moerjan. This points at affective ties that could be formed in domestic environments like a boarding school.

Finally, in the fragment Jonkhoff repeatedly refers to the Christian faith that had supposedly greatly influenced Moerjan. The teacher even mentions that Moerjan’s death was ‘a gain’ for the girl, perhaps because she was not suffering anymore, or because she, in the view of the teachers, died after having been introduced to Christianity.

4. Provenance of the sources

1. Atria, Kennisinstituut voor Emancipatie en Vrouwengeschiedenis, Amsterdam, archive Internationaal Archief voor de Vrouwenbeweging, collection Stichting Christelijke Huishoudscholen voor Indonesische Meisjes (SCHIM), inv no. 1-49.

This is the archive of the support committee of the KWS, the so-called Ladies’ Committee, that was based in Amsterdam. The foundation that continued the work of the Ladies’ Committee after Indonesian independence was disbanded in 2009, and the archive was transferred to Atria because of its relevance for the history of women’s missionary work.

2. Utrechts Archief, Utrecht, Archive Generaal Depuutschap voor de Zending, Zendingsbureau, Zendingscentrum en aanverwante instellingen van de Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland (GDZ), entry number 1133, inv. no. 3086-3122.

In this archive, that documents the missionary activities of the Reformed Churches, there are a few additional sources on the school, including newsletters that teachers sent out to alumni. It is unclear how this collection ended up in this archive.

3. J.H. Kuyper, ‘Hoe Moertinah op de Koningin-Wilhelminaschool kwam’. In De kruisvlag in top. Zendingsvertelboek voor school en huis, edited by J. Hobma, H.A. v.d. Hoven van Genderen, and Annie C. Kok, 342–52. Zwolle: H.H. Kok Bzn., 1926.

This is a fictionalised account of the experiences of a student at the KWS, written by Johanna Kuyper for a children’s book. This book was published with the aim of sparking enthusiasm for the Protestant mission among Dutch school children. The name of the protagonist is likely inspired by Moertinah, the older sister of Moerjan who entered the school before her.

4. Kerkeraad van Amsterdam, ed. Vijf-en-twintig jaar zendingsarbeid te Djocja. Amsterdam: Holland, 1925.

This memorial book gives an overview of the activities of the activities of the Reformed Mission in Yogyakarta. It situates the KWS among the several schools that the mission established in the city and the broader Yogyakarta region.

5. Raden Adjeng Kartini, Door duisternis tot licht. Gedachten over en voor het Javaansche volk van wijlen Raden Adjeng Kartini, ed. J.H. Abendanon, 3rd ed. (The Hague: Luctor et Emergo, 1912), 45–60. Available online through the National Library of the Netherlands: https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=MMUBL07:000002642.

In this fragment of her famous posthumously published book, Kartini describes her personal experiences with pingit, the practice of secluding marriageable priyayi girls in their home.

5. Postcolonial (Dis-)Continuities

There are no more archival traces of Moerjan, her brother Soedar or her sister Moertinah after Moerjan’s death and based on the archive it is impossible to say how her family fared during the remaining decades of colonial rule and later. The KWS was converted into a coeducational Christian primary school in the early 1930s. We do know that several KWS alumni stayed in touch with one another, and that some women continued to correspond with their former teachers until after decolonisation.

The history of the support committee, however, shows clear postcolonial continuities. In 1949, the name of the support committee was changed into SCHIM, Stichting Christelijke Huishoudscholen voor Indonesische Meisjes (Foundation for Domestic Science Schools for Indonesian Girls). By 1967, the foundation supported ten girls’ schools in Java and Sulawesi, where the Reformed mission was active as well. The foundation also supported two teacher training colleges in Solo and Yogyakarta and provided the schools with Christian magazines, Bibles, and materials for needlework lessons. By 1999, there were only four schools left in Central Javanese cities: Yogyakarta, Surakarta, Magelang and Purwokerto. The foundation was dissolved in 2009 because of a lack of donors. Only the school in Purwokerto continued to receive support from the Christian humanitarian foundation Stichting Pikulan, which is based in the village of Surhuisterveen in Friesland. This work continues until today.

6. Silences

Apart from the specific facts about Moerjan’s life – her parents’ motivations for sending her to the KWS, the life of her siblings and other family members, the reason and date of her return to the school – there are several questions that so far remain unanswered. We have only a very general idea of the numbers of students that went to the KWS, the Koningin Emma School in Solo, and the domestic science school Juliana van Stolberg School that was opened by the same support committee in Yogyakarta in 1927. It is also unclear which life trajectories alumni followed after graduation, and if, and how, their Christian education influenced this. Finally, more research is needed to determine the postcolonial continuities of the missionary work more clearly.

7. Call for input

I would be very interested to get in touch with people whose family members, perhaps even their mothers or grandmothers, were educated at elite Christian schools for Indonesian girls before and after decolonisation. I would also be interested in getting into a conversation with people whose families were part of the priyayi elite in the Dutch East Indies, to learn about their families’ relationship to Western education in the colonial period and beyond.

8. Links to other life stories

Life story about Sister Xaveria: another priyayi girl who lived in a Christian missionary school on Java, even though this was a Roman Catholic school.

9. Futher reading

Archival collections relating to Moerjan and the KWS:

- Atria Amsterdam, collection Stichting Christelijke Huishoudscholen voor Indonesische Meisjes (SCHIM), inv. no 1-49.

- Utrechts Archief, Archive Generaal Depuutschap voor de Zending, Zendingsbureau, Zendingscentrum en aanverwante instellingen van de Gereformeerde Kerken in Nederland (GDZ), entry number 1133, inv. no. 3086-3122.

Published source material (more links to be added):

- Kerkeraad van Amsterdam, ed. Vijf-en-twintig jaar zendingsarbeid te Djocja. Amsterdam: Holland, 1925.

Plus articles in Christian media:

- Christelijk Vrouwenleven

- Christelijk Schoolblad

- Thimotheüs

Fiction:

- Kuyper, J.H. ‘Hoe Moertinah op de Koningin-Wilhelminaschool kwam’. In De kruisvlag in top. Zendingsvertelboek voor school en huis, edited by J. Hobma, H.A. v.d. Hoven van Genderen, and Annie C. Kok, 342–52. Zwolle: H.H. Kok Bzn., 1926.

Academic articles:

- Kirsten Kamphuis. ‘An Alternative Family: An Elite Christian Girls’ School on Java in a Context of Social Change, c. 1907-1939’. BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 135, nos. 3-4 (2020) pp.133-157. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.10870

This open access article presents a detailed analysis of the Koningin Wilhelmina School and the child separation practices associated with it.

- Elsbeth Locher-Scholten. ‘Colonial Ambivalencies: European Attitudes towards the Javanese Household (1900-1942)’. In Women and Households in Indonesia: Cultural Notions and Social Practices, edited by Juliette Koning, Marleen Nolten, Janet Rodenburg and Ratna Saptari, pp. 28-44. Richmond: Curzon, 2000.

This book chapter analysis the way in which Dutch colonial officials and Christian reformers interpreted Javanese family life. The author focuses on priyayi families specifically.

- Agnes de Boer. ‘Kuyper, Henriëtte Sophia Suzanna’. In Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland. http://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/vrouwenlexicon/lemmata/data/KuyperHenriette. Published 2017.

This article provides background information about the life of Henriëtte Kuyper, who was one of the leading figures in the support committee of the KWS.

- Jean Gelman Taylor. ‘Kartini’. in Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland. http://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/vrouwenlexicon/lemmata/data/Kartini. Published 2018.

This article provides biographical information about Raden Ajeng Kartini, a famous priyayi female author.

10. Author

Kirsten Kamphuis. Cluster of Excellence Religion and Education, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster. Email address: Kirsten.kamphuis@uni-muenster.de

Notes

- Source: Atria Kennisinstituut voor Emancipatie en Vrouwengeschiedenis (hereafter Atria), Amsterdam, Internationaal Archief voor de Vrouwenbeweging (hereafter IAV), archive Steuncomité Christelijke Huishoudscholen voor Indonesische Meisjes (hereafter SCHIM), inventory number 6, ‘Tweede Verslag van het Comité van Bijstand voor de “Koningin-Wilhelmina-School”, Christelijke School voor Meisjes uit den Javaanschen Adelstand te Jogjakarta, van 1 Juli 1907 – 30 Juni 1909’.[↩]

Moerjan born

Moerjan as a boarding student at the school

Moerjan moves to Bandung

Moerjan dies