Maria Cecile Soetilah subsequently sister Xaveria Pantjawidagda O.S.U., one of the first Javanese women to enter the religious order of the Ursulines of the Roman Union in the Dutch East Indies in the 1930s

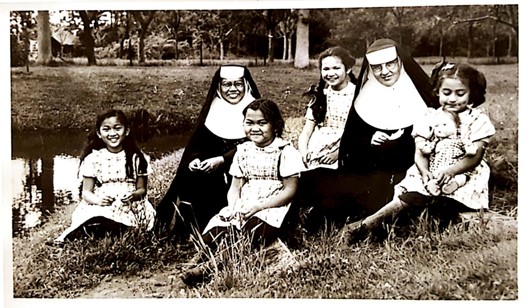

Maria Cecile Soetilah (later, sister Xaveria Pantjawidagda O.S.U.) on the right of the image was one of the first Javanese women to enter the religious order of the Ursulines of the Roman Union in the Dutch East Indies in the 1930s

1. Abstract

Maria Cecile Soetilah attended the Mendut school in Java, which was run by the Franciscan sisters of Heythuysen. This was a Roman Catholic religious order that maintained multiple schools in the Dutch East Indies. The school at Mendut was meant to provide a Christian education to the daughters of elite Javanese families (priyayi). In 1932, Cecile entered the novitiate of the Ursuline sisters of the Roman Union at Bandung. This was a different Roman Catholic religious order that also operated multiple schools in Java. She eventually became an Ursuline sister. Sister Xaveria was an active and relatively well-known sister within the international Ursuline community.

2. Timeline

2. Keywords and Timeline

Timeline: Cecile is born in Muntilan (5 October 1912), Cecile starts school at the H.I.S. (Hollands-Inlandse-school, Dutch-Native school) in Mendut (until 1924), Cecile graduates from the fröbelkweekschool at Mendut (April 1929), Cecile works in Malang and Surabaya (c. 1929-1931), Cecile enters as a postulant with the Ursuline Sisters of the Roman Union and adopts the religious name ‘Xaveria Pantjawidagda’ (1932), sister Xaveria writes an article in a local newspaper (1948), sister Xaveria gives a speech at a conference in Bandung (1955-1956), sister Xaveria dies in Surabaya (27 December 1980).

3. Cecile’s story

Transcription:

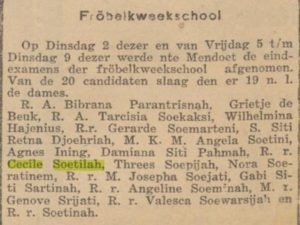

Fröbelkweekschool

Op Dinsdag 2 dezer en van Vrijdag 5 t/m Dinsdag 9 dezer werden te Mendoet de eindexamens der fröbelkweekschool afgenomen. Van de 20 candidaten slaag den er 19 n. l. de dames.

R. A. Bibrana Parantrisnah, Grietje de Beuk, R. A. Tarcisia Soekaksi, Wilhelmina Hajenius, R.r. Gerarde Soemarteni, S. Siti Retna Djoehriah, M. K. M. Angela Soetini, Agnes Ining, Damiana Siti Pahmah, R. r. Cecile Soetilah, Threes Soepijah, Nora Soeratinem, R. r. M. Josepha Soepijah, Nora Soeratinem, R. r. M. Josepha Soejati, Gabi Siti Sartinah, R. r. Angeline Soeminah, M. r. Genove Srijati, R. r. Valesca Soewarsijah en R. r. Soetinah.

Translation:

Fröbelkweekschool.

On Tuesday the 2nd and from Friday the 5th to Tuesday the 9th of this month, the final exams of the Fröbelkweekschool in Mendut were held. Of the 20 candidates 19 passed, namely the ladies.

R.A. Bibrana Parantrisnah, Grietje de Beuk, R. A. Tarcisia Soekaksi, Wilhelmina Hajenius, R.r. Gerarde Soemarteni, S. Siti Retna Djoehriah, M. K. M. Angela Soetini, Agnes Ining, Damiana Siti Pahmah, R. r. Cecile Soetilah, Threes Soepijah, Nora Soeratinem, R. r. M. Josepha Soepijah, Nora Soeratinem, R. r. M. Josepha Soejati, Gabi Siti Sartinah, R. r. Angeline Soeminah, M. r. Genove Srijati, R. r. Valesca Soewarsijah en R. r. Soetinah.

This is a newspaper announcement published in De locomotief on 12 April 1929. The announcement describes the final examinations of the girls-only fröbelkweekschool (school for the training of kindergarten teachers) in Mendut in 1929. From other sources we know this school was run by the Franciscan sisters of Heythuysen. De locomotief was a newspaper published in Semarang, a city in North-Middle Java located north-west of Mendut. It reported both local news about Java and international news. The announcement was published on a page devoted to local news from midden-Java (central Java). In this period, the newspaper often published advertisements, news and information about schools in Java. 1

In the announcement we see the name ‘Cecile Soetilah’. From other sources we know that Cecile was sister Xaveria’s given name. The newspaper announcement shows that she studied at the fröbelkweekschool in Mendut – run by the Franciscan sisters of Heythuysen – and graduated in April 1929. From another source we know that she started out as a pupil of the Hollands Inlandse School (Dutch-Native School), a boarding school for Javanese girls also run by the Franciscan sisters. From the same source we also know that sister Xaveria attended a vocational school for Nuttige handwerken (useful handicrafts) before starting her education at the fröbelkweekschool.

From the literature on this school, we know that it was mostly attended by daughters of Javanese priyayi girls. The priyayi were the Javanese nobility and usually had family members working in the colonial administration.2 The newspaper announcement also gives the letters ‘R. r.’ in front of her name. This stands for ‘Raden Roro’, which translates as ‘unmarried daughter’, a title for members of priyayi families. This confirms that sister Xaveria’s family was of relatively high social standing, and this was probably the reason why she was able to attend the H.I.S. Besides this, we can see the background of students at the school in Mendut reflected in this newspaper announcement: most of the girls mentioned seem to have a Javanese name.

For a large part, the Mendut schools were intended to transform the children of the Javanese elite in several ways. Western, or, more specifically, Christian cultural values and knowledge were transmitted to them, thus hopefully transforming them into devoted Catholics. They were also taught the Dutch language, which was the main language at the school. This meant that they could more easily fit within colonial structures. Furthermore, the pupils trained by the kweekschool were intended to become local intermediaries, who could further convert and transmit Christian culture and knowledge to the rest of the indigenous population. The boarding school was designed to separate the pupils from their Islamic families and/or communities, so they could more easily be converted and transformed into said intermediaries.3 Seeing as sister Xaveria received her education at these schools, she must also have been subjected to these strategies of child separation at the schools in Mendut.

Source 2: Mère Ildephonse O.S.U., ‘Eerstelingen’, Sint Claverbond; Uitgave der Paters Jezuïeten ten bate hunner missie op Java 45 (1933): pp. 13-15,

Transcription:

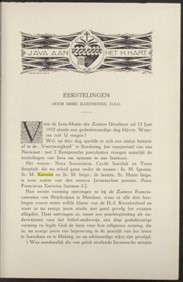

EERSTELINGEN

DOOR MÈRE ILDEPHONSE, O.S.U.

Voor de Java-Missie der Zusters Ursulinen zal 12 Juni 1932 steeds een gedenkwaardige dag blijven. Waarom zult U vragen ?

Wel, op dien dag speelde er zich een stukje historie af in de “Voorzienigheid” te Bandoeng, het voorportaal van ons Noviciaat; met 2 Europeesche postulanten vroegen namelijk de eerstelingen van Java om opname in ons Instituut.

Het waren: Nora Soeratinem, Cecile Soetilah en Trees Soepijah, die nu schuil gaan onder de namen : Sr. M. Ignatio, Sr. M. Xaveria en Sr. M. Inigo; de laatste, Sr. Marie Inigo, is eene zuster van den eersten Javaanschen priester. Pater Franciscus Xaverius Satiman S.J.

Hun eerste vorming ontvingen ze bij de Zusters Franciscanessen van Heijthuijsen te Mendoet, waar ze alle drie leerlingen waren eener zelfde klasse van de H.-I. Kweekschool en waar ze na eenige jaren studie met goed gevolg het examen aflegden. Daar ontvingen ze, naast een prachtopleiding als onderwijzeres voor het fröbel-onderwijs, een diep godsdienstige vorming en legde God de kiem voor hun religieuze roeping, die ze, na eenige jaren van beproeving in de practijk van het leven te Soerabaia en te Malang, nu op edelmoedige wijze zijn gevolgd.

’t Was aandoénlijk die van geluk stralende Javaansche meisjes te zien in hun donkerbruine sarong en lichtblauwe kabaia met daaroverheen het postulanten-kraagje en kruisje en op het hoofd de postulanten-sluier.

Ze waren zoo blij eindelijk hun doel bereikt te hebben, en toen de eerste van het groepje, die van huis was moeten vluchten, omdat men haar in het huwelijk wilde doen treden, in de kapel voor het beeld der H. Maagd neerknielde om haar religieuze vorming geheel en al onder bescherming van onze machtige

[Start tekst onder afbeelding]

Sr. M. Ignatio. Sr. M. Inigo. Sr. M. Xaveria.

De 3 eerste Javaansche postulanten der Zusters Ursulinen

[Einde onder afbeelding]

Moeder te stellen, kon ze van geluk maar met moeite aan een eind komen.

En nu, na meerdere maanden postulaat, nu ze het mooie, maar moeilijke Ursulinen-leven leerde kennen en waardeeren, nu worden ze met den dag gelukkiger en hebben maar één wensch: degelijke religieuzen te worden, om zóó Christus te doen uitstralen naar haar landgenootjes op onze scholen.

Ze geven, nu ze postulant zijn, les in onze H.I.S. te Bandoeng, en het is merkwaardig hoe veel vrijer de kinderen met hen praten en hen vragen stellen, waarmee ze bij eene Europeesche Zuster niet zouden aankomen.

Hier zien wij een keer te meer hoe het Javaansche kind behoefte heeft aan Javaansche Zusters, waar het niet met wantrouwen tegenover staat, waar het rustig mee kan praten, en die het gemakkelijker begrijpen.

Mogen vanuit het centrum der Java-Missie, waar met zoo’n noesten vlijt gearbeid wordt aan de bekeering van het volk, nog meerdere edelmoedige zielen den weg vinden naar ons noviciaat: moge het dagelijksch “Adveniat Regnum Tuum” van deze onze eerstelingen verhooring vinden en nog velen doen volgen, om met edelmoedigheid en offer den Priester te helpen uitbreiden Christus’ Rijk op Java.

DIE VELEN TOT DE GERECHTIGHEID ONDERWIJZEN ZULLEN SCHITTEREN ALS STERREN IN DE IMMERDURENDE EEUWIGHEDEN

DAN 12.3

FIRST ONES

BY MÈRE ILDEPHONSE, O.S.U.

For the Java Mission of the Ursuline Sisters 12 June 1932 will always be a memorable day. Why, you would ask?

Because, on that day, a piece of history played out in the ‘Voorzienigheid’ in Bandung, the vestibule of our Novitiate; together with 2 European postulants the first ones of Java asked for entrance into our Institute.

They were: Nora Soeratinem, Cecile Soetilah and Trees Soepijah, who now use the names: Sr M. Ignatio, Sr M. Xaveria and Sr M. Inigo; the last, Sr Marie Inigo, is a sister of the first Javanese priest, Father Franciscus Xaverius Satiman S.J.

They received their first confirmation with the Franciscan sisters of Heythuysen in Mendut, where all three students attended the same class at the H.-I. Kweekschool and where, after some years of study, they successfully completed their final exams. There, besides excellent training to become teachers in fröbel-education, they received deep religious formation, and God sowed the seed for their religious calling, which they have now followed in a noble manner, after some years of being tested in the practice of life in Surabaya and Malang.

It was moving to see the happiness radiating from the Javanese girls in their dark brown sarong and light blue kebaya with their postulant collars and crosses on top and the postulant veils on their heads.

They were so happy to have finally reached their goal, and when the first of the group, who had had to flee from home, because she was being subjected to an arranged marriage, kneeled in the chapel before the statue of the Holy Virgin to put her religious formation entirely under the protection of our powerful

[Caption underneath the picture]

Sr M. Ignatio. Sr M. Inigo. Sr M. Xaveria.

The 3 first Javanese postulants of the Ursuline Sisters

[End of caption]

Mother, she was so happy it was difficult for her to stop.

And now, after several months of postulancy, now they have come to know and appreciate the beautiful, but difficult Ursuline life, they are becoming happier each day and have only one wish: to become decent religious people, to radiate Christ to their little countrymen [in Dutch, the diminutive is used] in our schools.

Now they are postulants, they teach at our H.I.S. in Bandung, and it is curious how much more freely the children talk to them and ask them questions with which they would not approach a European sister.

Again we see how the Javanese child has a need for Javanese Sisters, whom it does not distrust, to whom it can talk calmly and who understand it more easily.

May even more noble souls find the way to our Novitiate from the core of the Java-Mission, where the conversion of the people is being worked on with such diligent assiduity: may the daily ‘Adveniat Regnum Tuum’ of these our first ones be heard and make many more follow, to help the Priest expand Christ’s Kingdom on Java with nobility and sacrifice.

THOSE THAT EDUCATE THE MANY TO RIGHTEOUSNESS WILL SHINE LIKE STARS IN PERPETUAL ETERNITY

DAN 12.3

This is an article published in the missionary magazine Sint Claverbond; Uitgave der Paters Jezuïeten ten bate hunner missie op Java. The Sint Claverbond was an organisation founded in the 1880s that supported the mission in Java.4 The magazine was published by the Dutch Jesuits in the Netherlands from 1889 until 1946.4 It contained articles about the Roman Catholic mission in Java, which were important to gain support and attention for mission activities in Java. The article was written by a ‘Mère Ildephonse’. It is likely that this is Mère Ildefonse de Jongh, who was novice meesteres (novice mistress) for the Ursulines of the Roman Union in Bandung during this period.5

The article consists of text, and a picture of sister Xaveria and two other Javanese postulants named Sr M. Ignatio and Sr Marie Inigo. Their worldly names, Nora Soeratinem and Trees Soepijah, also appear in the announcement published in De locomotief. As is said in the article, they studied together at the schools in Mendut, where they were educated and where ‘God sowed the seed for their religious calling’. This refers to the aforementioned child separation practices in the Mendut schools. In the article, these are justified by mentioning that the first of the group fled from home because she was going to be subjected to an arranged marriage. It is unclear who exactly this refers to, but it is unlikely to be sister Xaveria, since we know from another source that her parents were Christian.6 The article mentions that the three sisters asked for entrance into the order on 12 June 1932, at the same time as two European girls. They did so after a period of ‘beproeving in de practijk van het leven’ (being tested in the practice of life) in Surabaya and Malang. It is probable that, because of their background as teachers, they worked at an H.I.S. during this time. We are, however, left with some questions. Who are the European girls and what is their relationship with the three Javanese novices? Why did the three decide to enter into the Ursuline order and not the Franciscan sisters of Heythuysen, where they received their education? The three women completed their postulate, which usually lasted six months. After the postulate they would have started their novitiate period.7 During this period, the three postulants/novices taught native children at the H.I.S. in Bandung. According to Ildephonse, their Javanese background made them less susceptible to distrust by native children.

The picture of the three girls is interesting because they are shown in traditional Javanese clothing (sarong and kebaya) combined with postulants’ clothing. This indicates an acceptance or acknowledgement of their Javanese cultural background, at least at this stage of their life within the Ursuline order. It could also have been a means of differentiating them from other, European postulants. It is unclear whether or why they wanted to wear the sarong and kebaya underneath their robes, or if they were asked to do so. We do know that at the schools in Mendut Javanese clothes were sometimes accepted or encouraged for the pupils in the 1920s. 8 It is possible, however, that the three girls were asked to wear traditional clothing to make the picture more interesting or noticeable to Dutch audiences.

What is obvious throughout the article is a sense of pride. The author describes these three girls as eerstelingen (first ones), which was an important milestone in their mission to ‘expand Christ’s Kingdom on Java’. The sisters were so proud that they chose this event to be showcased to Dutch supporters of the Catholic mission. These three young women are presented as proof of the progress of mission work in the Dutch East Indies. This pride is further evidenced by variants of this photo and other articles about these girls and their time as novices, that pop up in another missionary magazine and in a short history of the Ursulines, as well as by one large, prominent photo of the three as novices in a photo album of different Ursuline congregations in Java. 9 Thus, the three seem to have been used as poster children for the progress and importance of the Catholic mission.

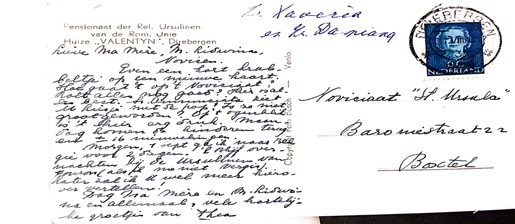

Source 3: A postcard of Sister Xaveria Pantjawidgda

Transcription:

Pensionaat der Rel. Ursulinen Sr. Xaveria

Van de Rom. Unie et Sr. Dapiang [?]

Huize “VALENTYN”, Direbergen

Noviciaat “St. Ursula”

Baroniestraat 22

Boxtel

Lieve ma Mère, M. Lidwina, Novicen.

Even een kort krabbeltje op een nieuwe kaart.

Hoe gaat ’t op ’t Noviciaat? Rolt alles nog goed? Hier is alles best.

Sr. Amumaiata [?] ziet u Liesje met de pop? Is ze niet groot geworden?

Op ’t ogenblik is ’t hier erg druk. Maandag komen de kinderen terug en ± 16 nieuwelingen.

Morgen, 1 sept ga ik naar België voor 2 dagen. ‘k blijf overnachten bij de Ursulinen van Fouron (als ik me niet vergis).

Later zal ik U wel meer hierover vertellen!

Dag ma Mère en M. Lidwina en allemaal, vele hartelijke groetjes van Thea

Translation:

Pension of the Rel. Ursulines Sr Xaveria

of the Rom. Union et Sr Dapiang [?]

‘VALENTYN’ House, Direbergen

Novitiate ‘St Ursula’

Baroniestraat 22

Boxtel

Dear ma Mère, M. Liswina, Novices.

Just a short note on a new card.

How is it at the Novitiate? Is everything alright? Here everything is fine.

Sr Amumaiata [?] do you see Liesje with the doll? Hasn’t she grown?

It is very busy here at the moment. On Monday the children will come back and ± 16 newcomers.

Tomorrow, 1 Sept, I’m going to Belgium for 2 days. I will stay at the Ursulines of Fouron (if I am not mistaken).

I will tell you more about this later!

Bye ma Mère and M. Liswina and all, many warm regards from Thea

This is a postcard sent to the novitiate in Boxtel, the Netherlands by someone called Thea. The picture seems to have been taken at Huize Valentyn in ‘Direbergen’. This is likely a typographical error and should be ‘Driebergen’, an Ursuline monastery in the Netherlands. Huize Valentyn was a boarding school for girls run by the Ursulines.

The photograph on the front of the postcard shows sister Xaveria and another unknown sister who is referred to as Sr Dapiang [?]. They are sitting on a field beside a river and are accompanied by four children with a seemingly Indo-European or Javanese background. We only know the name of the girl with the doll: ‘Liesje’, which is mentioned on the back of the card. It is possible that these children were attending Huize Valentyn as pupils. In another photograph they are pictured in a larger group photo with other girls (most of whom are white).

From other sources we know that sister Xaveria travelled to Driebergen and Amsterdam between 1949 and 1951. According to those sources, she travelled there for the purpose of further study. 10 From these sources we know that was educated at an Europese Kweekschool (European teacher training school), received an education in religious studies in Amsterdam, and was enrolled in the M.O.A. Paedagogiek (bachelor’s degree in Pedagogy). 11 Further records concerning her education have not been found as of yet. This raises the question which degrees she eventually obtained while in the Netherlands, if any. The available sources do show that sister Xaveria was a determined student and committed to educating herself. They also show that she wanted to teach upper-class and/or European children, as is shown by her getting an education at an Europese Kweekschool. 12

The photograph is also interesting for another reason. Sister Xaveria and the non-European children are placed together and printed onto a postcard that is meant to be sent to others. It is interesting that they chose sister Xaveria and these children for this purpose. Sister Xaveria and the children must have been seen as a point of pride and interest for the Ursulines. In other words, sister Xaveria was again pushed forward as a poster child of the missionary work of the Ursuline order. We have also found similar pictures, including more postcards, of sister Xaveria and these children in the archives, further emphasising the way in which the children and sister Xaveria were made into objects of publicity.

Source: Maria Xaveria Pantjawidagda O.S.H., ‘Missiehoekje’, De gong 11 (1948): p. 13

Transcription:

MISSIEHOEKJE

Mijn ouders en grootouders en ik zelf, wij zijn gedoopt door grote pioniers van de Missie: als Pastoor Hoevenaars, Pastoor van Lith enz. Opgegroeid temidden van een geweldige activiteit kon het niet anders, of ik leerde ook wat voor Jezus over te hebben. Mijn kloosterroeping heb ik aan de missionarissen te danken.

In deze tijd is het goed eens te zeggen, dat Indonesia veel aan Nederland te danken heeft. Ik kan het niet met zulke uitgezóchte woorden zeggen, maar ik hoop, dat U me zult begrijpen: Indonesia is mijn Vaderland; maar Nederland is mijn Moederland. Van Nederland heb ik, en met mij zoveel anderen, een goed ontvangen van veel grotere en hogere waarde dan wat ter wereld ook.

Ik hoop, dat Nederland zijn taak t.o.v. Indonesia trouw blijft. Ik zal zelf op mijn plaats het mijne proberen te doen om de grote missiegedachte overal ingang te doen vinden. Daar heb ik nu prachtig de gelegenheid voor, nu ik aan het hoofd sta van een grote school van 400 leerlingen. Deze kinderen verstaan alleen Javaans en Maleis, zij willen graag Nederlands leren en kregen het vanaf de vierde klas. ledereen wil naar school met Nederlands als voertaal.

Maar er is geen plaats genoeg en dus proberen de ouders met allerlei slimmigheden om hun kinderen er toch te krijgen. Ze drillen hen, zodat ze op de gebruikelijke vragen in het Hollands kunnen antwoorden. Aan een van die kinderen vroegen we eens: “Hoe heet je?” “Phaly” was het antwoord en toen met opzet een andere als de gewone vraag, “Waar is je neus?” en zonder aarzelen, kwam het antwoord “In de Lawoestraat”.

Groteren maken niet meer van die vergissingen, maar ze vertellen je b.v. wanneer een ander de kluts kwijt raakt: „O Zuster, ze is helemaal weggeklutst (historisch). Maar ik heb een leuk idee. Kunnen de kinderen in Holland geen scholen in Indonesia adopteren? Practisch komt dit dan hierop neer: bidden voor een bepaalde school in de missie; zo nu en dan schriftelijk contact door leuke kaarten en briefjes.

Voor onze kinderen is het een stimulans om Nederlands te leren en tevens wordt er de sympathie voor edelmoedig Katholiek Nederland door bevorderd.

Ook zou de jeugd b.v. voor een Kerstfeest of voor een ander feest kunnen sparen. Geen geld, maar zelfgemaakte kleinigheden, schilderijtjes, eigengemaakte prentenboeken, uitgezaagde kribbetjes e.d. Ook zijn kledingstukken heel welkom.

Ik hoop, dat onze Javaanse meisjes dan terugschrijven. Ik zelf had vroeger ook lang correspondentie met een meisje uit Nijmegen, vanaf de tweede klas van de lagere school af al. We groeiden samen op, eerst stuurde ze me prentenboeken, later maakte ze me blij met gedichten van Henriette Roland Holst. Ik genoot altijd van haar brieven en ik leerde de Nederlandse taal waarderen en voelde veel voor de Nederlandse letterkunde.

Alvast dank ik de edelmoedige jeugd van Holland voor alles, wat zij voor Java doet en vraag voor me zelf een gebedje om veel tot Gods glorie en het heil van mijn volk te kunnen werken en velen te kunnen voeren tot Christus.

MARIA XAVERIA PANTJAWIDAGDA O.S.H.

Translation:

MISSION CORNER

My parents and grandparents and myself, we were baptised by great pioneers of the [Catholic] Mission, such as Father Hoevenaars, Father van Lith, etc. Raised amid great activity, I couldn’t help but learn to do something for Jesus. I have the missionaries to thank for my monastic vocation.

In these times it is good to say, for once, that Indonesia has a lot to thank the Netherlands for. I am not able to say it eloquently, but I hope that you will understand me: Indonesia is my Fatherland; but the Netherlands is my Motherland. From the Netherlands I, and so many others, have received a gift of much greater and higher value than anything else in the world.

I hope that the Netherlands stays loyal to its task in relation to Indonesia. I will try with my own position to make sure the missionary ideals find their entrance everywhere. I now have a wonderful opportunity to do so, now I am the head of a large school of 400 pupils. These children only understand Javanese and Malay, they are eager to learn Dutch, which they are taught starting from the fourth class. Everyone wants to go to a school with Dutch as its main language.

But there is not enough room and thus the parents try to get their children into the school through all kinds of clever tricks. They train them so that they can answer the usual questions in Dutch. We once asked one of the children: ‘What is your name?’ ‘Phaly’ was the answer and then we deliberately switched one of the usual questions to ‘Where is your nose?’ and without hesitation, they answered ‘On Lawoestraat [name of a street]’.

The older ones do not make mistakes like that anymore, but they tell you, for example when another child loses their marbles: ‘O Sister, she has completely unmarbled (historical). But I have a nice idea. Is it not possible for the children in Holland to adopt schools in Indonesia? In practice it comes down to this: pray for a certain school in the mission; now and then send some nice cards and notes.

For our children it will be a stimulus to learn Dutch and at the same time it will promote sympathy for the noble Catholic Netherlands.

The children can also save up for, say, a Christmas party or another party. Not money, but homemade knick-knacks, paintings, homemade picture books, little handcrafted cribs and so on. Pieces of clothing are also very welcome.

I hope that our Javanese girls will then write back. I myself also had a long-lasting correspondence with a girl from Nijmegen, starting in the second class of primary school. We grew up together, first she sent me picture books, later she delighted me with poems by Henriette Roland Holst. I always enjoyed her letters and I learned to appreciate the Dutch language and felt much affiliation with Dutch literature.

In advance I thank the noble youth of Holland for everything they do for Java and ask for myself a little prayer, so I can work for God’s glory and the salvation of my people and drive a lot of them towards Christ.

MARIA XAVERIA PANTJAWIDAGDA O.S.H.

This is an article written by sister Xaveria that was published in the magazine De gong in 1948. This was a magazine that was published between 1947-1950 by the organisation Katholieke Actie Vrouwelijke Jeugd [Catholic Action Female Youth] in Breda. Not much information can be found about this organisation, but based on the name and the articles in the magazine it seems to have been an organisation focused on activities for young Catholic girls in the Netherlands. The article itself is part of a section about the Catholic mission.

In the article, sister Xaveria writes quite extensively about her own past, which tells us a lot about her. She mentions being baptised by well-known missionaries in the Dutch East Indies and being inspired by them towards a religious vocation. She also professes her respect and love for the Netherlands, while at the same time staying loyal to Indonesia, calling the Netherlands her motherland and Indonesia her fatherland. Interestingly, however, at the end of the article she seems to still identify with the people of Indonesia, asking the readers of De gong to pray for her so she can work towards the ‘salvation of her own people’. She apparently feels connected to both of these cultures. She also mentions her own time as a student, where she had contact with a student from Nijmegen, who was about the same age and sent her letters and a book that sparked her love for Dutch literature and poetry.

More importantly, she gives us some information about her current life, especially her current experiences as a teacher. She mentions being the head of a school of 400 students. This is a very big responsibility and points to the highly regarded reputation and status sister Xaveria must have had within the Ursuline community. We know that, at the time, sister Xaveria was attached to the ‘Juanda’ congregation, which is one name for the monastery of Santa Maria, Jakarta.11 It is not entirely clear which school she was the head of, but she mentions that the students speak Javanese and Malay and are also taught Dutch. In other words, over a decade after her novitiate, sister Xaveria was still teaching mostly ‘non-European’ children, either because of her own choice or because the other Ursulines felt she would be most suited there.

To help the children in her school learn the Dutch language, and to foster sympathy, she asks the children of the Katholieke Actie Vrouwelijke Jeugd to ‘adopt’ schools in Indonesia. She asks them to write and pray for the schools and requests that they send her things like cribs and picture books for the students. In other words, sister Xaveria, who herself was an object of child separation practices, was now herself an important and active agent in perpetuating child separation. She did so by teaching Indonesian children the Dutch language and Christian culture, working towards the ‘salvation’ of the people of Indonesia.

Transcription:

Hoe kan de religieuze opvoedster in een asrama [slaapzaal] de christelijke geest brengen?

Door eerst zelf volop christen te zijn in de ware betekenis. Als christen-persoonlijkheid zal ze dan vanzelf een christelijke sfeer om zich heen scheppen, dus ook in het asrama. Die christelijke sfeer is dan een middel om in de kinderen de christelijke geest te bevorderen, en dat komt dan weer ten goede aan de christelijke sfeer.

Om de christelijke sfeer in het asrama te versterken, geeft onze Moeder de H.Kerk middelen te over. Zij die ons tot taak heeft gegeven de jeugd christelijk op te voeden, staat ook klaar ons de middelen daartoe te geven. Welke zijn o.a. die middelen? Heel de schat van waarheden, heel de rijkdom van de katholieke leer, alle genademiddelen en bovenal God zelf, Christus, Zijn Moeder, Gods engelen en heiligen! Onze taak is het dat alles te doen kennen, waarderen en liefhebben – niet alleen aan de katholieke kinderen, maar ook aan de niet-katholieke – Wij moeten de kinderen het leven meegeven de kennis van de eeuwige waarheden, juiste en klare ideeën over God, de Verlossing, de zonde, de hemel, enz. Ze zullen er een sterk een sterk onwankelbaar houvast aan hebben in de moeilijkheden, die ze toch zeker ook zullen ondervinden. We weten, hoe zwaar de beproevingen soms kunnen zijn: zo zwaar dat alleen eeuwige waarden de mensen staande kunnen houden. Wat is het heerlijk, dat wij in staat gesteld zijn om haar die steun te geven.

Translation:

How can a religious educator bring the Christian spirit into an asrama [dormitory]?

Firstly, by being fully Christian in the true sense. As a Christian personality she will then automatically create a Christian atmosphere around herself, so too in the asrama. That Christian ambience is then a means of promoting the Christian spirit in the children, and that in turn benefits the Christian atmosphere.

In order to strengthen the Christian atmosphere in the asrama, our Mother has given the Holy Church resources in abundance. She who has given us the task of educating the youth in a Christian way, is also ready to give us the means to do so. What are those resources? All the many truths, all the riches of Catholic teaching, all the means of grace and, above all, God Himself, Christ, His Mother, God’s angels and saints! Our job is to make them know, appreciate and love all these things – not only for the Catholic children, but also for non-Catholics – We must give to the children knowledge of the eternal truths, the right and clear ideas about God, Redemption, sin, heaven, etc. With these things, they will gain a strong and unshakable foothold for coping with the difficulties that they will surely experience. We know how severe the trials can be at times – so severe that only eternal values can sustain people. It is so wonderful that we are able to give them that support.

This is an excerpt of a speech given by sister Xaveria at a conference for sisters in Bandung. This conference was the second of its kind and was attended by many different Catholic religious orders of women that were active in Indonesia. It was organised by the Ursuline sisters. Most of the attendees were active sisters who worked in education or hospitals. The full document contains a long list of sisters who were present at the conference. Sister Xaveria is not mentioned in this list due to the many sisters of the Ursuline order who were present at the conference (who are listed as ‘lokale oversten’, or local superiors). It also features an overview of the sixteen different talks that were given at the conference. Most of them pertain to the topic of education.

The excerpt is further proof of sister Xaveria’s high standing within the Ursuline order and of the higher education she received in the Netherlands. It is unlikely that she was merely put forward or asked to do this speech due to her Javanese background in this instance. From other sources we know that she was a council member in the congregation of Madiun and a teacher at the SGA-school St Immaculata. This was, and still is, a Roman Catholic University. What exactly she taught there is unclear as of yet. We do know that she was part of that congregation for ten years (from 1951 to 1961).

The excerpt also shows that Christianity was an important part of her ideas concerning the education of girls. She views the teachings and dogma of the Roman Catholic church as a tool for spreading Christianity in boarding schools. Further on in the speech she states that modernity forces teachers to modernise their methods, but that the core of upbringing stays the same and will always be Christianity. All of this shows that she was an active missionary who really tried her best to convert her pupils to Christianity. In other words, she was truly an ‘intermediary’ in the process of conversion. Furthermore, she went from being an object of child separation practices to being a proponent and carrier of these practices.

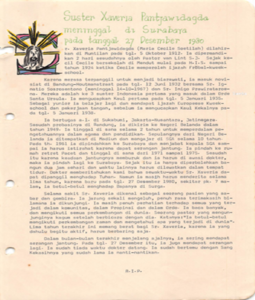

Source: Menologium of Sr Xaveria Pantjawidagda, O.S.U., from the Ursulines of the Roman Union provincialate in Bandung.

Transcription:

Suster Xaveria Pantjawidagda

mininggal di Surabaya pada tanggal 27 December 1980

Sr. Xaveria Pantjawidagda (Maria Cecile Soetilah) dilahirkan di Muntilan Pada tgl. 5 Oktober 1912. Ia dipermandikan 2 hari sesudahnya oleh Pastor van Lint S.J. Sejak kecil Cecile bersekolah di Mendut mulai pada H.I.S. sampai tahun 1924 ketika Cecile memperoleh ijazah Fröbel-kweekschool.

Karena merasa terpanggil untuk menjadi biarawati, ia masuk novisiat di Bandung-Houtmanstraat pada tgl. 12 Juni 1932 bersama Sr. Ignatio Sosrosentono (meninggal 14-10-1967) dan Sr. Inigo Prawirataroena. Mereka adalah ke 3 suster Indonesia pertama yang masuk dalam Orde Santa Ursula. Ia mengucapkan Kaul pertama pada tgl. 5 Januari 1935. Sebagai yunior ia belajar lagi dan mendapat ijazah Europeese Kweekschool dan pekerjaan tangan, sebelum ia mengucapkan Kaul Kekalnya pada tgl. 5 Januari 1938.

Ia bertugas a.l. di Sukabumi, Jakarta-Nusantara, Jatinegara. Sesudah probasinya di Bandung, ia dikirim ke Negeri Belanda dalam tahun 1949. Ia tinggal di sana selama 2 tahun untuk memperdalam pengetahuannya dalam agama dan pendidikan. Sepulangnya dari Negeri Belanda ia ditempatkan di Madiun dan mengajar di SGA selama 10 tahun. Pada th. 1961 ia dipindahkan ke Surabaya dan menjabat kepala SGA sampai ia harus istirahat karena dapat serangan jantung. Ia pindah ke rumah retret Pacet dan tinggal di sana dari 1971 sampai 1975. Sesudah itu karena keadaan jantungnya memburuk dan ia harus di awasi dokter, maka ia pindah lagi ke Surabaya. Sejak itu ia hanya diperbolehkan bangun dua jam sehari dan waktu lainnya harus dilewatkan dalam tempat tidur. Dokter memberitahukan kami bahwa sewaktu-waktu Sr. Xaveria dapat dipanggil menghadap Tuhan. Namun ia masih harus menderita selama lima tahun, karena baru pada tgl. 27 Desember 1980, sekitar pk. 7 malam, ia betul-betul menghadap Bapanya di Surga.

Selama sakit Sr. Xaveria dikenal sebagai seorang pasien yang sabar dan gembira. Ia jarang sekali mengeluh, penuh rasa terimakasih bilamana ia dikunjungi. Ia masih penuh perhatian terhadap semua yang terjadi dalam komunitas, dalam Propinsi dan dalam Ordo. Ia baca banyak, dan mengikuti semua perkembangan di dunia. Seorang pastor yang mengunjunginya kagum setelah berbicara dengan dia. Katanya: “Ia betul-betul mengikuti perkembangan zaman dan mengetahui apa yang terjadi di dunia”. Lima tahun terakhir ini memang berat bagi Sr. Xaveria, karena ia yang dahulu begitu aktif, harus berbaring saja.

Dalam bulan-bulan terakhir menjelang ajalnya, ia sering mendapat serangan jantung. Pada tgl. 27 Desember itu, ia juga mendapat serangan lagi. Ia sudah tiada waktu dokter datang. Ia sudah bertemu dengan Sang Kekasihnya yang sudah lama ia nanti-nantikan.

Translation:

Sister Xaveria Pantjawidagda

died in Surabaya on 27 December 1980

Sr Xaveria Pantjawidagda (Maria Cecile Soetilah) was born in Muntilan on 5 October 1912. She was baptised 2 days later by Pastor van Lint S.J. As a child, Cecile attended school in Mendut starting at H.I.S., until 1924, when Cecile earned a Fröbel-kweekschool degree.

Feeling her calling to be a sister, she entered the novitiate at Bandung-Houtmanstraat on 12 June 1932 together with Sr Ignatio Sosrosentono (died 14-10-1967) and Sr Inigo Prawirataroena. They are the first 3 Indonesian sisters to enter the Order of Santa Ursula. She took the first vow on 5 January 1935. As a junior she studied again and obtained a European Kweekschool degree and a handicrafts degree, before she took her eternal vows on 5 January 1938.

She served in Sukabumi, Jakarta-Nusantara, Jatinegara, among other place. After her probation in Bandung, she was sent to the Netherlands in 1949. She lived there for 2 years to deepen her knowledge of religion and education. On her return from the Netherlands she was stationed in Madiun and taught at the SGA for 10 years. In 1961 she was transferred to Surabaya and served as the head of the SGA until she had to rest due to a heart attack. She moved to the Pacet retreat house and lived there from 1971 to 1975. After that, because her heart condition deteriorated and she had to be monitored by a doctor, she moved to Surabaya again. After that, she was only allowed to get up for two hours a day and the rest of the time had to be spent in bed. The doctor told us that Sr Xaveria could be called before God at any time. But she still had to suffer for five years, because it was only on 27 December 1980, around 7 PM, that she actually came before her Father in Heaven.

During her illness Sr Xaveria was known as a patient and happy patient. She seldom complained and was full of gratitude when she received visitors. She is still attentive to everything that happens in the community, in the province and in the Order. She reads a lot and keeps up with all the developments in the world. A pastor who visited her was amazed after talking to her. He said: ‘She really keeps up with the developments of the times and knows what is happening in the world’. The last five years were hard for Sr Xaveria, because she used to be so active and was only allowed to lie down.

In the months leading up to her death, she often had heart attacks. On 27 December, she had another heart attack. There was no time for a doctor to come. She has met her Beloved, for whom she had been waiting for a long time.

This is a document called a menologium, which is drafted after the death of each sister of the Ursuline order.

From this source we discover the exact date of sister Xaveria’s death. We learn that the last ten years of her life were not without pain and anguish. There also seems to be a small error in the document. It states that Cecile obtained her degree from the Fröbelkweekschool at Mendut in 1924. This is contradicted by multiple sources. It could, however, also be a mistake in the translation of the document. It is more likely that 1924 is the year in which she finished her education at the H.I.S.

The source paints a rough picture of the course of her life. We learn the dates at which she took the first and the eternal vow and it mentions the different degrees she obtained during her life. It also mentions her time in the Netherlands, and indicates that she was ‘sent to’ the Netherlands. This raises multiple questions: Did she go of her own accord or was she indeed sent ‘away’, and by whom? Why was she ‘sent’ to the Netherlands? Also keeping in mind that a similar education was possible in the Dutch East Indies. Was she sent to the Netherlands so she would be taken out of her environment? In other words, was this a case of child separation practices being continued into adult life? The source does not mention whether she obtained any degrees while in the Netherlands. It does show us, however, that she obtained her degree at the Europese Kweekschool in the Dutch East Indies.

The source also gives us a rough idea of sister Xaveria’s life after her speech at the conference discussed above. She was stationed in Madiun from 1951, where she worked as a teacher for ten years. After this she was transferred to Surabaya where she served as head of the SGA, a school for tertiary education. Note how the words ‘stationed’ and ‘transferred’ do not ascribe any agency to sister Xaveria herself. However, the fact that she was the head of such a school, comparable to a small university in the Western world, says a lot. It means she was very high up in the Ursuline hierarchy, at least within this congregation. She worked as the head of this school until around 1971, when she had a heart attack. It seems as though the rest of her life was spent in declining health because of her heart condition. She moved to the Pacet retreat house, about which we know very little. The last five years of her life, sister Xaveria was bedridden until she finally died of another heart attack.

This source is also one of the few sources which mentions something about sister Xaveria’s character. It describes her as very active, at least before her health declined. Apparently, she was still committed to gaining knowledge about the world around her, evidenced by the fact that she ‘kept up with all the developments in the world’ and was also still interested in what happened ‘in the community, in the province and in the Order’. She is described as patient and happy, even during years of, what must have been, pain and anguish.

4. Provenance of the sources

Sources 1, 2 and 3 were found via Delpher, a database of digitalised newspapers, magazines and books, mostly in the Dutch language. The documents in the database are taken from various libraries, heritage institutions and scientific institutions. The site is maintained by the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (Royal library, KB), which is an independent national and public library which has as its mission to gather, preserve and make accessible everything that has been published in and about the Netherlands, for all people. 13 Delpher was started in 2013 to make the KB collections more accessible, not only for researchers but also in general for a historically interested public. 14 This was done in partnership with the university libraries of the Universities of Groningen, Leiden, Utrecht and Amsterdam, whose collections can also be found in Delpher. The launch of Delpher was financially supported by the Meertens Instituut [Meertens Institute], Metamorfoze, Stichting PICA and theDutch Research Council (NWO). The Meertens Instituut is an organisation that does research into Dutch culture and language.15 Metamorfoze is a national organisation that has as its purpose to preserve paper heritage material, to prevent the decay or destruction of paper heritage. It is financed by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. 16 Stichting PICA is an organisation that gives subsidies for scientific and public information provision. 17 NWO is also subsidised by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science and the Ministry. It finances research conducted at universities and public research institutes and tries to make connections between different projects, researchers and societal actors. It also performs research itself. 18

Sources 4 and 5 were found in the archive of the Ursulines of the Roman Union (O.S.U.), which has been given on loan to the Erfgoedcentrum Nederlands Kloosterleven (ENK, Heritage Centre for Dutch monastery life). The archives of about one hundred religious communities have been given on loan to the ENK, which preserves and makes accessible the archives to ‘belangstellenden’ (stakeholders). The ENK itself is housed in the monastery of St Agatha in Cuijk, the Netherlands.

The archive consists of material from the houses in the Netherlands that are part of the O.S.U. Before the Roman Union was formed around 1900, these houses maintained their own archives.19 ‘The archive consists of material from the houses in the Netherlands that are part of the O.S.U. and the bestuursarchief (governance archive of the O.S.U. province of the Netherlands). Before the Roman Union was formed around 1900, the houses maintained their own archives. Therefore, the oldest material can be found in these house archives and not in the governance archive, which was created in 1928, when this province was founded. Before that time, the Dutch houses of the O.S.U. were part of the province of the Netherlands, Belgium and England. The archive of that province can most likely be found in Belgium. For those who wish to gain access to the O.S.U. archives at the ENK, permission must be obtained from either the O.S.U. or the ENK, depending on the age of the material. If a record is less than 75 years old, the O.S.U. needs to give their permission. If it is older, only the ENK needs to give permission.

Source 5 was found in the house archive of Driebergen and source 4 was found in the governance archive of the Dutch province. This particular archive also contains some material from houses outside the Netherlands, including from the mission in Indonesia.

The sixth source was found in the archive of the provincialate of Bandung, a city in contemporary Indonesia where one O.S.U. house was based. We obtained a copy of this source from a contact of Dr Maaike Derksen (Radboud University).

5. Postcolonial continuities

After decolonisation, Xaveria continued to try to further the mission and kept working in education in Indonesia. After being subjected to child separation in her youth and being influenced and inspired towards a Christian monastic life, away from the traditional Javanese community, she herself became an agent for the mission and perpetuated child separation practices. She did this, for example, as the head of a school for Indonesian children, by teaching them the Dutch language.

For that reason, although we do not have many sources on her life, Xaveria herself can be seen as a sort of link between the colonial order and the new postcolonial order. She was educated, taught and inspired by the European missionaries and was driven by this to educate and convert other Indonesians. The many children that were taught by her, including, for example, Liesje, who was with her in Driebergen, lived their lives, formed by Xaveria’s work. The 400 pupils who attended her school in Indonesia were also likely influenced by her and her efforts in education and character building.

There are also other continuities to be found. Xaveria taught at Juanda (or Noordwijk). Although it is not clear at what exact school she taught here, the Ursulines still maintain a school for female children that is directly descended from the Ursuline schools from the colonial period. This is called the ‘St Ursula Catholic School’. The Ursulines also still maintain a school and monastery for girls in Bandung, the same city where Xaveria did her novitiate.

Interestingly, the novitiate of the Ursuline sisters in Bandung also seems to still exist. On the webpage of this novitiate, the three first Javanese girls that did their novitiate with the Ursulines are mentioned by name: Sr Xaveria, Sr Inigo and Sr Ignatio. Even to this day, the Ursulines seem to be quite proud of their first Javanese sisters. Xaveria’s role as a kind of poster child for the Ursulines has apparently not completely ended, even after her death.

6. Unanswered questions and silences

A question that remains is how many Javanese girls followed in Xaveria’s footsteps and entered the Ursuline order – or another religious order – themselves. It would be especially interesting to know whether Javanese girls from less elite backgrounds entered (and were allowed to enter) into monasterial life. Perhaps connecting sister Xaveria’s story to other vignettes will allow us to see the bigger picture. It might, however, be more difficult to trace these other girls, seeing as they were not poster children like ‘the first three’.

A second question is how Xaveria came to make the choice to enter a religious order. She herself mentions that she was inspired by the great pioneers of the Catholic mission, but we do not get more insight into whether, for example, the Mendut schools played a role in stimulating her to choose a religious life. A related question is: why did Xaveria enter the Ursuline order? She was educated by the Franciscan Sisters of Heythuysen. Why not try to gain entry there?

Sr Xaveria and Sr Inigo seemed to have achieved a relatively high status in the community of the Ursuline sisters. Why was this the case? The larger question is whether girls with a Javanese background often gained a high status in religious orders, and how. As the first Javanese sisters it seems they were given a lot of positive attention, but what was this like for other Javanese sisters within the Ursuline order, or other religious orders of women?

7. Collaboration and conversation: call for input

We are interested in finding more information, especially concerning the education at the Mendut schools. Yearbooks, for instance, as sources where student names are shown, could be very helpful. We would also like to learn more about the way in which Javanese women looking to enter the Ursulines or other religious orders of women were dealt with in this period. Sources or stories about other women who underwent a novitiate or postulate during this period would be a welcome contribution. Besides this, we are interested in finding out whether there are people who remember sister Xaveria, Inigo or Ignatio. Do you have any stories or sources to share with us about these sisters? Please do not hesitate to contact us.

All other feedback, criticism or suggestions are also welcome!

8. Vignettes linked to this child

The vignette on Bido by Marleen Reichgelt – another indigenous child whose life was shaped by the Roman Catholic mission in the Dutch East Indies.

The vignette on Raden Roro Moerjan by Kirsten Kamphuis – another life story of a priyayi girl.

9. Further reading

- For an interesting news story about postcolonial continuities, see: https://www.ucanews.com/story-archive/?post_name=/2007/02/22/catholic-students-publish-spiritual-experiences&post_id=28822#.

- For a very well-researched and interesting chapter about the schools in Mendut, see: Maaike Derksen, Embodied Encounters: Colonial Governmentality and Missionary Practices, Java and South Dutch New Guinea, 1856-1942. PhD diss., Radboud University, 2021, pp. 65-104.

10. Authors

Rayza Zander and Simon van Duijn, MA students, Radboud University

Kirsten Kamphuis, Cluster of Excellence Religion and Education, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster.

Email address: Kirsten.kamphuis@uni-muenster.de

Notes

- For example: ‘Examen vrouwelijke handwerken’, De locomotief, 29 November 1930, p. 10, http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=MMKB23:001726053:mpeg21:p00010; Keboemen, ‘Opening particuliere fröbelschool’, De locomotief, 24 July 1939, p. 16, http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=MMKB23:003468043:mpeg21:p00016; ‘Examens: Examencommissies Nuttige Handwerken’, De locomotief, 8 January 1935, p. 3, http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=MMKB23:001761010:mpeg21:p00003, https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/16670467.[↩]

- Maaike Derksen, Embodied Encounters: Colonial Governmentality and Missionary Practices, Java and South Dutch New Guinea, 1856-1942 (PhD diss., Radboud University, 2021), pp. 70, 82-84.[↩]

- Derksen, Embodied Encounters, pp. 88-93.[↩]

- http://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/zendingoverzeesekerken/RepertoriumVanNederlandseZendings-EnMissie-archieven1800-1960/gids/organisatie/306249489.[↩][↩]

- Kroniek Noordwijk, p. 44; Gedenkboek van de Religieuzen Ursulinen Der Romeinsche Unie op Java, p. 217.[↩]

- Maria Xaveria Pantjawidagda O.S.H., ‘Missiehoekje’, De gong 11 (1948): p. 13, http://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=MMKDC05:004174011:00001.[↩]

- Brochure Weltevreden Ursulinen.[↩]

- Derksen, Embodied Encounters, pp. 91-93.[↩]

- Onze Missien, Bandoeng. Zegen. 126-127, 129. No. 1, March 1933, vol. 5. Cor Unum; Buku Perayaan 100 Tahun Suster Ursulin; 10399 ENK.[↩]

- Informatiekaart, p. 2; Personalia, p. 30.[↩]

- Informatiekaart, p. 1.[↩][↩]

- Derksen, Embodied Encounters, chapters 2 and 3.[↩]

- Koninklijke Bibliotheek, ‘Organisatie en Beleid’, accessed 1 June 2021, https://www.kb.nl/organisatie/organisatie-en-beleid.[↩]

- Yuri Visser, ‘Universiteitsbibliotheken en KB lanceren online dienst Delpher’, Historiek, 20 November 2013, https://historiek.net/universiteitsbibliotheken-en-kb-lanceren-online-dienst/38699/.[↩]

- Meertens Instituut, ‘Missie, visie en kernwaarden’, accessed 2 June 2021, https://www.meertens.knaw.nl/cms/nl/over-het-meertens-instituut/missie-visie-en-kernwaarden.[↩]

- Metamorfoze, ‘Geschiedenis’, accessed 2 June 2021, https://www.metamorfoze.nl/geschiedenis.[↩]

- Surf,‘Stichting Pica’, accessed 2 June 2021, https://www.surf.nl/cooperatie-surf/stichting-pica.[↩]

- NWO, ‘Wat NWO doet’, accessed 2 June 2021,https://www.nwo.nl/wat-nwo-doet.[↩]

- More information about the sources and the history of the order can be found here: Archieven.nl, ‘Inleiding’, accessed 2 June 2021, https://www.archieven.nl/nl/zoeken?miadt=1212&mizig=210&miview=inv2&milang=nl&micols=1&micode=AR-Z117&mizk_alle=weltevreden#inv3t1.[↩]

Cecile is born in Muntilan

Cecile starts school at the H.I.S. (Hollands-Inlandse-school, Dutch-Native school) in Mendut

Cecile graduates from the fröbelkweekschool at Mendut

Cecile works in Malang and Surabaya

Cecile enters as a postulant with the Ursuline Sisters of the Roman Union and adopts the religious name ‘Xaveria Pantjawidagda’

sister Xaveria writes an article in a local newspaper (1948)

sister Xaveria gives a speech at a conference in Bandung

Sister Xaveria dies in Surabaya on 27 December 1980