Indigenous children of paper and ink Torn between competing paternal authorities (1908-1920)

1. Abstract

This vignette discusses literary counterparts of real-life indigenous children who were forcefully displaced from their birth families and villages, to illuminate how contemporaneous Dutch-language children’s literature supported colonial practices of child separation. These practices were strongly dependent on financial and moral support from the home front, and a great variety of discourses were mobilised to garner this support, such as missionary magazines, religious tracts and educational books targeting Dutch-speaking children in the colony and the metropole, most notably textbooks and children’s novels. This vignette features three child characters from children’s novels set in the Indies by the once widely read author Marie C. van Zeggelen, who had spent twenty-six years of her adult life there.

2. Timeline

3. Marie C. van Zeggelen and fictional colonial children

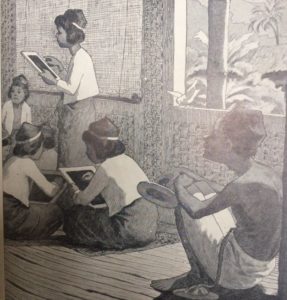

Meet La Ballo, Din and Bo, early twentieth-century Buginese children who spent their childhood on and around South-Sulawesi – called ‘Celebes’ during Dutch colonial rule. Even though they were growing up at opposite ends of the Buginese social hierarchy, La Ballo being a descendant of an ancient royal dynasty of indigenous leaders, while Bo and Din were consigned to the humble position of child slaves, they, nevertheless, had a lot in common. None of them were securely settled in their families of origin. They all struggled through conflicts of loyalty to competing paternal figures, which involved them in a series of perilous displacements, to the point that their lives were hanging in the balance. In all three cases, their conflicting loyalties could only be resolved by the intervention of Dutch authorities, who provided the stability and safety that their indigenous surroundings could not give them.

In fact, La Ballo, Bo and Din are relatives, in that they are all the brainchildren of the Dutch author Marie C. van Zeggelen (1870-1957), as creatures of paper and ink rather than flesh and blood. Van Zeggelen was the highly prolific and widely read author of forty-two books, twenty-four of which were set in the Dutch East Indies, where Van Zeggelen spent twenty-six years of her adult life. Twelve of these books were written for Dutch children around the age of ten. Judging from the number of reprints, her children’s novels were highly appreciated, especially the nine stories that featured the Indies. Van Zeggelen’s output was mostly in the area of narrative fiction, but it also included some autobiographical sketches and a biography of Raden Adjeng Kartini (Kartini, 1945), a daughter of the Javanese nobility and an advocate of women’s rights.

La Ballo, Din and Bo are the leading characters in, respectively, De gouden kris (The Golden Sword, 1908), De schat van den armen jongen (The Poor Boy’s Treasure, 1913) and Het zeerooversjongetje (The Pirates’ Boy, 1920). The novels are clearly informed by the author’s own stay on Celebes/Sulawesi as the wife of Hendrikus Adrianus Kooij, captain in the Dutch colonial army (KNIL) and leader of the Boni expedition of 1905-1906, which was embarked on to ‘pacify’ the ever-unruly kingdom of Boni, situated on the coast of South-West Sulawesi. Boni had always been a fertile breeding ground of resistance against Dutch colonial rule and the target of a whole series of punitive military interventions that aimed to subdue the rebels with armed violence, from 1825 up to the infamous ‘police action’ led by captain Raymond Westerling in 1947, which was an important episode in the two colonial wars that the Dutch fought to retain their much prized colony in the wake of the Second World War.

Van Zeggelen’s stay on Celebes was thus closely entangled with Dutch colonial politics, although she kept herself aloof from her husband’s military occupations, preferring an anthropologist’s stance towards her new surroundings instead. Van Zeggelen took a profound interest in the living circumstances, cultural practices and narrative traditions of the Buginese, immersing herself in them up to the point that she felt entitled to write her children’s novels from indigenous perspectives exclusively. In the novels mentioned, readers are made to feel that they are looking at the world through the eyes of La Ballo, Bo and Din. It is supposedly ‘their’ thoughts, feelings and perceptions that shape the representation of events – or, rather, that is the game of make-believe that van Zeggelen presents to her reading audiences.

De gouden kris takes its cue from a real-life event that took place during the 1905 Boni expedition. The defeated radja of Boni, La Pawawoi, donated the possessions of his son who had died in battle to a KNIL leader, namely his sword (‘kris’), the sword’s sheath and a cap, reputedly to express his gratitude that his life and those of his family were spared by the Dutch conquerors. A (golden) sword, the phallic symbol of the radja’s masculine authority, courage and wealth, also plays a central role in De gouden kris. La Ballo is the adopted son of his uncle, Aroe Lipa, an indigenous leader who subjected himself to the Dutch colonial regime, as opposed to his brother, Deng Pabéle, who fled into the mountains to fight a guerrilla war against the Dutch, leaving his family behind, including his son La Ballo.

Deng Pabéle and his followers are branded as mere plunderers by the narrator of De gouden kris, rather than as political rebels, even though they are clearly in the process of organising armed resistance against the colonial regime from their hiding places in the impenetrable mountain region. Deng Pabéle’s brother Aroe Lipa, on the other hand, collaborates with the Dutch government, who demand of him that he deliver his brother to them. This presents a difficult dilemma for Aroe Lipa, who is forced to choose between loyalty to his family and obedience to the foreign rulers. Reluctantly, Aroe Lipa chooses the latter and promises to seek out his brother and betray Deng Pabéle’s hiding place, handing over his sword as collateral to the Dutch authorities in the presence of La Ballo. The latter is so shaken by his adoptive father’s loss of (symbolic) power and authority that he decides to go look for Deng Pabéle himself, so that Aroe Lipa’s sword may be returned to him as soon as possible. Thus, La Ballo’s conflict between loyalty to his biological and his adoptive father is settled in favour of the latter, who seems to be more deserving of paternal authority than the former, a choice that mirrors Aroe Lipa’s decision, who favors the Dutch over his own family because of a complex mixture of motives. While Aroe Lipa is very critical of the taxes the colonial regime imposes on the indigenous population, which are significantly higher than the tithes of their indigenous leaders, he nevertheless acknowledges that the Dutch also bring ‘good’ things to the island, such as improved infrastructure, hygiene, health care and education.

Being only eleven years old, La Ballo sorely underestimates the difficulty of tracking down his father in the wilderness of the mountains, which makes him an easy prey for the rebels, who use him for their own recruitment purposes by presenting him as a semi-divine child who has come down from up above to support their fight against the Dutch. And all this is condoned by the rebel leader Deng Pabéle, who thereby disqualifies himself as a parent in the eyes of the narrator of the novel. The rebels succeed in mobilising hundreds of desperate mountain dwellers, whose houses and ways of life are about to be destroyed by the colonial government, with the help of the divine figurehead of La Ballo, who seems to have fallen out of the sky. In the meantime, the KNIL have taken matters into their own hands as Aroe Lipa has failed to deliver his brother, and the rebels meet a miserable fate when an opium addict amongst their ranks betrays them to the Dutch army, who execute all of the rebels, women and children included, after they refuse to surrender.

Meanwhile, La Ballo’s life is miraculously saved by some thorny bushes that break his fall as he is dragged into a ravine by Deng Pabéle, where the latter ends his own life. La Ballo is literally hanging from a cliff when his ‘true’ father Aroe Lipa finds him. Sword and son are now returned to their rightful places in Aroe Lipa’s household, and the novel ends with a vision of La Ballo as the personification of a rather vague, but hopefully better future for the governance of the Indies: ‘… zal hij wellicht worden als gij; een goed bestuurder van zijn volk. Ja, dat zal hij worden maar … ook als gij, Aroe Lipa, zal hij lijden, want het is zwaar, bitter zwaar voor een trotsch karakter, het juk te dragen dat een ander ras hem oplegt’ (he might well become just like you, a just leader of his people. Yes, that’s what he will become but … also just like you, Aroe Lipa, he will suffer as well, because it is hard, very hard for a proud character to bear the yoke that another race has imposed upon him’ (De gouden kris, p. 211). La Ballo shall become a wise leader one day, the narrator predicts, but he will remain under the tutelage of the Dutch, just like Aroe Lipa before him. The narrator’s ambivalence about the legitimacy of colonial rule clearly comes out in this passage. The narrative voice seems to abide by a ‘might makes right’ principle: the white Dutch race just happens to be superior to the Buginese, and therefore it is inevitable that the one will rule over the other. Wise people like Aroe Lipa understand and accept the inevitable, even though they do so with considerable criticism of the Dutch, who impose heavy dues on the indigenous population and destroy their villages if these get in the way of infrastructural innovations, a criticism the narrator seems to share.

De schat van den armen jongen provides a perspective from below, by featuring eight-year-old Din as its main character, who belongs to the lowest of the low as an orphan and the slave and cymbal player of the prince Aroe La Tanroewa, who is the equal of Din in age only. Din’s job is to surround the prince with noise to chase away evil spirits. The two boys grow up together, and Din is quite content with his humble but comfortable position at the prince’s court, until the latter turns twelve. It was assumed that children would be able to fend for themselves from this age onwards, so at that point, Din has outlived his use and is ruthlessly discarded. In his despair over his abandonment, Din tries to steal the cymbals that had once served both him and the prince so well. When he is found out, he is forced to flee from his village and native land to the wilderness high up the mountains, where he lives for two years or so with the ‘tree-people’, who live in treehouses and sustain themselves by hunting and gathering and by means of the occasional spoils of the ‘pagorra’, or robbers. While the prince’s father Aroe Padaëli has subjected himself to Dutch colonial rule, the tree-people try to stay away from it as much as they possibly can. As in De gouden kris, those who do not accept Dutch governance are depicted as ordinary thieves. Din sets about civilising the tree-people by teaching them how to cultivate rice, transforming them from hunter-gatherers into farmers. He is quite successful in these efforts and, as a consequence, he grows in authority and power within the local community, becoming known as ‘Mahera’ (the wise one) and developing into the right-hand man of their ruler Arie Pong.

Din’s civilising project is suspended when their village is visited by Aroe Padaëli and his retinue, as well as a platoon of KNIL soldiers, who come to sniff out the ‘pagorra’. Din is now torn between his sympathy for the tree-people and their somewhat incompetent leader Arie Pong on the one hand, and his former guardians on the other. When the pagorra are about to launch a nocturnal attack on his former countrymen, his oldest loyalty wins out and he raises an alarm to prevent the onslaught. This intervention counterbalances his former fall from grace and he is allowed to return home, where he acquires a more enduring position at court. His alliance with the prince is renewed and the book ends with their plan to go on a trip to Java together, the ‘country of civilisation’ as the narrator calls it, which promises to have an uplifting effect on both of them. Thus, fatherless Din was forced to shift his allegiance from Aroe Padaëli and son to Arie Pong, the self-styled robber-king, and back again, thanks to the sustained efforts of the Dutch to pacify unruly and uncivilised indigenous nations.

Just like De gouden kris, Het zeerooversjongetje is based on real-life events, namely the life story of the indigenous convert Petrus Kafiar, to which at least two other children’s books have also been devoted. Bo lives a humble, but happy life with his family on the isle of Banggai, close to Celebes and the Soela isles (Moluccas). However, this peaceful life is disrupted when their village is raided by Alfoer pirates from Halmaheira, another Moluccan island, while the men of the village had all gone away to fell sago trees in the jungle. In their absence, the women and children are captured and abducted to the Sultanate of Ternate, while the pirate leader (the ‘kimalaha’) furtively picks out the ‘best’ ones for himself, in this case Bo and his friend Lodi. Bo is now completely cut off from his family and native land and consigned to the household of the kimalaha as his servant, together with Lodi. Although their treatment is not bad at all, Lodi, in particular, pines for her former home. Their lives take a turn for the better when a ‘strong man’ with a ‘Great Book’ crosses their path. Overpowering the kimalaha through the strength of superior moral character, this charismatic man (a barely disguised reference to the protestant missionary Johannes Lodewijk van Hasselt) gives Bo the courage to reveal that he and Lodi are being retained in the kimalaha’s household against their will, and that the other women and children of their village have been abducted to Ternate. The missionary manages to persuade the kimalaha to collaborate with him in tracking down the other enslaved people of Bo’s village, and eventually manages to ransom all of them.

The crucial question now becomes what Bo shall do: return to his native village, together with his mother, grandmother and little sister, or remain in the household of the missionary, whom he calls ‘Father’, and who teaches him many wonderful new things, such as reading, writing and taking care of the sick and disabled, something for which Bo appears to have a particular inclination and talent. The final episode of the novel belabours the point that Bo is given a completely free choice here, in contrast to his forced displacement from his village to the household of the kimalaha. Not a single word is breathed all throughout the novel about Bo’s real father, who had gone off into the woods in search of sago just before the raid, as if Bo is a fatherless child, who has now finally found a paternal figure who is truly worthy of the name father, in that he is truly capable of protecting the child and helps Bo to find his true vocation in life rather than merely using him for his own purposes, as the indigenous leaders of the kimalaha and the Sultan are in the habit of doing. After some hesitation, Bo decides to stay with the missionary, and to receive training as a medic.

4. Provenance of the sources

Van Zeggelen’s novels are still available through www.boekwinkeltjes.nl.

The stories analysed here are:

- Marie C. van Zeggelen. De gouden kris. 1908. Amsterdam: Scheltema & Holkema, 1928.

- Marie C. van Zeggelen. De schat van den armen jongen. 1913. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Scheltema & Holkema, n.d.

- Marie C. van Zeggelen. Het zeerooversjongetje. 1920. The Hague and Jakarta: G. B. van Goor Zonen, 1954.

5. Postcolonial (dis)continuities

Marie van Zeggelen belonged to the enlightened, progressive intellectual elite of her day. She was a staunch advocate of the Ethical Policy for the Dutch East Indies, together with other authors and scholars, such as Augusta de Wit, C. van Vollenhoven, C. Th. van Deventer, Nellie van Kol and, last but not least, C. Snouck Hurgronje, the famed anthropological expert on Islam and the Indies. Her novels stood out through their sustained interest in indigenous folklore, customs, beliefs and cultural practices, as well as through the centrality of ‘indigenous’ perspectives and voices. Van Zeggelen represents the entanglement of Dutch colonials with indigenous leaders through repeatedly highlighting their similarities. Both indigenous and colonial rulers exploit the local population through heavy taxation, but the Dutch use this money for infrastructural improvements, education, hygiene and health care, while local rulers only use the tithes for boosting the magnificence of their own royal households. Both indigenous and colonial rulers use violence to impose their authority on their subjects, which is presented by Van Zeggelen as natural and inevitable: the stronger will impose their will on the weaker, by force if needs be, and it is foolish to go against this. Both indigenous and colonial rulers take children out of their birth families and native villages, but indigenous people do so merely to enslave them, while the Dutch take indigenous children into their households to educate and uplift them. In other words, colonial authorities displace indigenous children for the latter’s own good, while indigenous nations displace children for merely egotistic motives. Displacing children is therefore not necessarily a bad thing per se in Van Zeggelen’s novels: it is represented as a widespread practice in and around Celebes and not even the child slaves Bo or Din have all that much to complain of. The problem with displacement is, rather, that indigenous children often lack moral guidance, for the only proper guidance they may expect to get is provided by paternal figures who are either Dutch, or accept Dutch rule, which not all indigenous leaders do, to their own detriment and that of their people. Thus, a pattern is established in Van Zeggelen’s colonial children’s novels (and in those of many other Dutch authors) which naturalises the separation of indigenous children from their native contexts: everyone is doing it, but the Dutch do it so much better, as child saviours, who are to be preferred to indigenous child snatchers.

For how long have children of paper and ink such as La Ballo, Bo and Din shaped the views of Dutch-language (child) readers on indigenous children and childhoods? According to Rob Nieuwenhuyzen, there was not a Dutch-speaking child in the East Indies who had not read Het zeerooversjongetje, a bold claim that also might apply to Dutch metropolitan children. Judging from the reprints of Van Zeggelen’s best-read children’s novel (1920, 1921, 1923, 1925, 1928, 1929, 1934, 1940, 1950, 1954, 1989) we may surmise that her popularity as a children’s book author peaked in the twenties, then remained on a plateau during the next three decades, to eventually dwindle to near-oblivion from the sixties onwards. There is a remarkable return to the literary scene with the reprint of 1989 in the series ‘Indische letteren’, but this should not surprise us too much. The 1989 edition is most likely a nostalgia reprint, a familiar phenomenon in the field of children’s literature, meaning that this edition was probably bought and read by adults who had read Van Zeggelen in their childhood and desired a momentary return to their childhood through their favorite books.

During the second half of the twentieth century, Dutch entanglement with the Indies more or less disappeared from public discourse. This is also the period in which the empire began to write back, to use Bill Ashcroft’s terminology, meaning that indigenous authors finally managed to gain access to Western book markets, as witnessed by the success of authors such as Chinua Achebe from Nigeria or Pramoedya Ananta Toer from the Republic of Indonesia. Rather than being spoken for, formerly subaltern groups began to speak for themselves in the fields of literature, politics and so forth. In the course of the eighties, the field of postcolonial studies was established primarily at Anglophone universities, with Dutch universities eventually following in their wake. What was once considered to be a noble thing to do, i.e. speak on behalf of those who supposedly cannot speak for themselves, now began to be increasingly frowned upon, as a practice that silences marginalised groups, even when this is not intended at all. In the field of children’s literature more specifically, the phenomenon of European, North-American, Scandinavian or settler-Australian novelists focalising their stories through indigenous child perspectives has come under serious attack, especially from the side of indigenous authors. For example, Australian Aboriginal author Anita Heiss has persistently defended the view that indigenous stories should be told by indigenous authors, if only because it is naive to assume that indigenous people would share all their (secret) knowledge and understandings with their (former) oppressors. This implies that hegemonic groups can never pretend to know subaltern groups other from the inside out. This means that the hallmark of Van Zeggelen’s children’s novels that she was once was lavishly praised for, i.e. the dominance of indigenous perspectives, has, by now, lost much of its credibility and respectability. With the advantage of hindsight, one might even observe that the conflicting loyalties that Van Zeggelen imputes to her child characters are in fact much more revealing of her own frame of mind. It was Van Zeggelen who was torn between her commitment to the Ethical policy for improving education, health care and infrastructure in the Indies to boost the wealth and well-being of the indigenous population on the one hand and the violent oppression of these people by the military expeditions of her husband that had brought her to the Indies in the first place on the other. The ambivalences and paradoxes that inhered in the Ethical Policy itself – which aimed to foster the independence of indigenous nations but expanded Dutch territory in the archipelago and intensified its surveillance and control in the meantime – are indicative of the tensions and conflicts within the mind of the author, who projected her own preoccupations onto her literary creations. In a way, this is what all literary authors do: ‘Madame Bovary, c’est moi’, as Gustave Flaubert famously claimed, but this stance becomes problematic when it prevents women writers from writing back to the images imposed upon them.

In the light of the above, one may legitimately assume that the life span of child characters such as La Ballo, Din and Bo is shortened wherever critical postcolonial and decolonial critical perspectives are gaining ground. In the end, however, this is up to readers to decide, who may not necessarily be familiar with or sympathetic to these perspectives.

6. Unanswered questions and silences

We are confronted with the difficulty that we do not know all that much about the reception of colonial children’s novels by juvenile audiences. Children do not write reviews, essays or literary histories, and, back then, they did not award literary prizes either. This makes inquiry into how children interpret and evaluate children’s novels highly challenging, especially where older children’s books are concerned, as one cannot interview these readers anymore to learn about their reading experiences.

7. Collaboration and conversation: call for input

Adults are often able to reproduce some memories of their childhood reading. For that reason, anyone who would like to share their childhood memories of reading Marie van Zeggelen’s novels (or related children’s novels about the East Indies) is warmly invited to share them with the author of this piece, whether they agree or disagree with the above: Lies.Wesseling@Maastrichtuniversity.nl.

8. Links to other vignettes

9. Further reading

Sources: Van Zeggelen’s novels are still available through www.boekwinkeltjes.nl.

- Marie C. van Zeggelen. De gouden kris. 1908. Amsterdam: Scheltema & Holkema, 1928.

- Marie C. van Zeggelen. De schat van den armen jongen. 1913. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Scheltema & Holkema, n.d.

- Marie C. van Zeggelen. Het zeerooversjongetje. 1920. The Hague and Jakarta: G. B. van Goor Zonen, 1954.

Children’s books that were inspired by the conversion story of Petrus Kafiar:

- Herbertina Benedicta La Bassecour Haan. Lasso: Een verhaal uit de zendingsgeschiedenis. Doetinchem: Misset, 1909.

- J. L. D. van Roest. Van slaaf tot evangelist: ‘Petrus Kafiar’. Utrecht: Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging, 1913. An adaptation for children of:

- Frans J. F. van Hasselt. Petrus Kafiar: De Biaksche evangelist. Utrecht: Utrechtsche Zendingsvereeniging, 1910.

Frans van Hasselt was the son of Johannes Lodewijk van Hasselt, and a missionary like his father.

Academic articles

- Elisabeth Wesseling and Jacques Dane. ‘Are “the Natives” Educable? Dutch Schoolchildren Learn Ethical Colonial Policy’. Journal of Educational Media, Memory and Society 10 (2018): pp. 28-43.

- Clare Bradford. ‘Reading Indigeneity: The Ethics of Interpretation and Representation’. In Handbook of Research on Children’s and Young Adult Literature, edited by Shelby A. Wolf, Karen Coats, Patricia Enrico and Christine A. Jenkins, pp. 331-341. New York and London: Routledge, 2011.

An exploration of the ethical complexities that beset Western appropriations of indigenous stories and narrative perspectives.

- Anita Heiss. ‘Aboriginal Children’s Literature: More Than Just Pretty Pictures’. In Just Words? Australian Authors Writing for Justice, edited by Bernadette Brennan, pp. 102-117. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 2008.

A passionate plea for reserving the representation of indigenous perspectives in narrative fiction for indigenous authors.

- Geertje Mak. ‘Children on the Fault Lines: A Historical-Anthropological Reconstruction of the Background of Children Purchased by Dutch Missionaries between 1863 and 1898 in Dutch New Guinea’. BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 135, nos. 3-4 (2020): pp. 29-55.

This is about the historical background to child removal and enslavement practices in New Guinea.

- Mavis Reimer and Elisabeth Wesseling, eds. ‘(Post-)Colonial Child Separation in Children’s Literature’. Special issue, International Research in Children’s Literature 13, no. 2 (2020).

Special issue on children’s literature about the separation of indigenous children from their native contexts in Sweden, the US and Canada.

- Jacques Vos. ‘Marie C. van Zeggelen’. In Lexicon van de Jeugdliteratuur, edited by Jan van Coillie, Wilma van der Pennen, Jos Staal and Herman Tromp. Groningen: Martinus Nijhoff, 1999.

A portrait of the author and a brief discussion of her work within the context of her day.

- Pamela Pattynama. ‘Wij kennen elkaar! Marie van Zeggelen, een Hollandse vrouw in Zuid-Celebes’. In Een tint van het Indische Oosten: Reizen in Insulinde 1800-1950, edited by Rick Honings and Peter van Zonneveld, pp. 153-161. Hilversum: Verloren, 2015.

An overview of Van Zeggelen’s writings for children.

- Elisabeth Wesseling. ‘In Loco Parentis: The Adoption Plot in Dutch-Language Colonial Children’s Books’. Tydskrif vir Letterkunde 46, no. 1 (2009): pp. 139-150.

Another article that reveals how deeply ingrained the tendency is in children’s fiction to portray indigenous children as essentially parentless, and, therefore, freely accessible to white families who are eager to take them in and to re-educate them. It deals with children’s novels about Surinam.

10. Author

Elisabeth Wesseling, professor of cultural memory, gender and diversity at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Maastricht University.

Lies.Wesseling@Maastrichtuniversity.nl

www.maastrichtuniversity.nl/CGD