Bido From guide to guru, the integration of children – and generations – into colonial societies

1. Abstract

In colonial societies, children played important intermediary and brokering roles between coloniser and the colonised, veering between different societal groups. A telling example concerns a Marind man named Bido1, who, as a young teenager, had served as a guide during the government explorations along the south coast of West Papua in 1905. Around 1910, he came to live with the Missionaries of Sacred Heart (MSC) in Merauke. Various photographs and documents attest to his life as one of their first local trustees and helpers. Bido’s life course shows how generations of cross-cultural intermediaries came into being.

2. Timeline

3. Bido’s story

Source 1: Bido as an anthropological subject

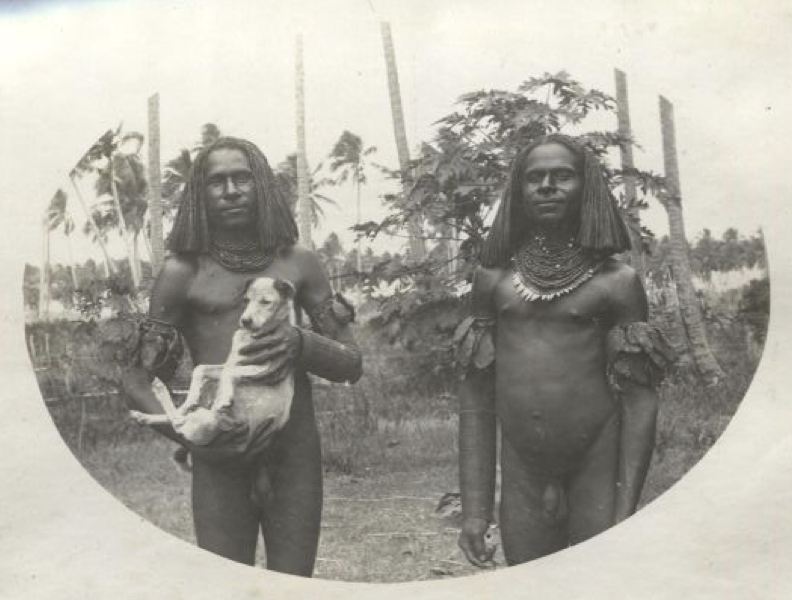

I first came across Bido in a collection of photographs taken for the purpose of anthropological research by the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (MSC) on the south coast of West Papua, then the Dutch colony of ‘Netherlands New Guinea’. At first sight, the photograph stood out because of the unusual scene it depicted. In a collection of photographs where most of the people were posing rigidly and with serious expressions on their faces, this image of two smiling and seemingly relaxed boys attracted my attention. Although the location where the photograph was taken is the same as some of the more ethnographical pictures – namely, the backyard of the mission station in Merauke – the picture is far more informal. The posture of the boys is relaxed but confident and the fact that they are looking directly into the lens of the camera and smiling gives the photograph a personal feel. The dog awkwardly propped up in the boy’s arms enhances the laid-back atmosphere and strengthens the perception of looking at a portrait of two individuals.

Upon closer inspection, the photograph stood out even more: it was the first photograph in the collection of someone of the Marind-anim community whose name was mentioned in the caption. And not just his name, but also his significance to the MSC: ‘Marind boys – with dog is Bido – head of the first group to be baptised’.2

In August 1905, four Dutch Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (in Latin: Missionarii Sacratissimi Cordis or MSC) arrived in Merauke, a military post on the south coast of West Papua that had been established just a few years earlier. Most sources on Bido’s life that I know of can be found in their archive. Two albums in the collection were almost exclusively dedicated to the anthropological photographs made by father H. Nollen between 1906 and 1909, reference numbers 20152 and 20153 in the archive.3

The albums are each titled Original inhabitants of the south coast of New Guinea around 1910.4 Together, they contain approximately 150 photographs. The picture of Bido can be found in album 20153. This album was most likely put together by father Nico Verhoeven (1896-1981, in Merauke from 1923-1935), as his signature can be found on the flyleaf. The albums are similar in both content and style, almost exclusively containing pictures of Marind-anim posing on the mission grounds or occasionally a beach village, accompanied by plain captions such as ‘Marind man 1910’, ‘Marind women 1910’ or ‘Marind girls’.

In the context of an album which had clearly been put together at least several years after the photographs had been taken and where most pictures were accompanied by very non-specific and even erroneous descriptions,5 this indicated that Bido stayed with the missionaries for a long period of time – from this first picture, which was taken around 1907, at least until after Verhoeven arrived in 1923. And indeed, Bido turns up several more times in the collection of photographs taken between 1906 and 1935. How did he get acquainted with the Catholic missionaries in the colonial settlement of Merauke and how did he end up being among the first to be baptised?

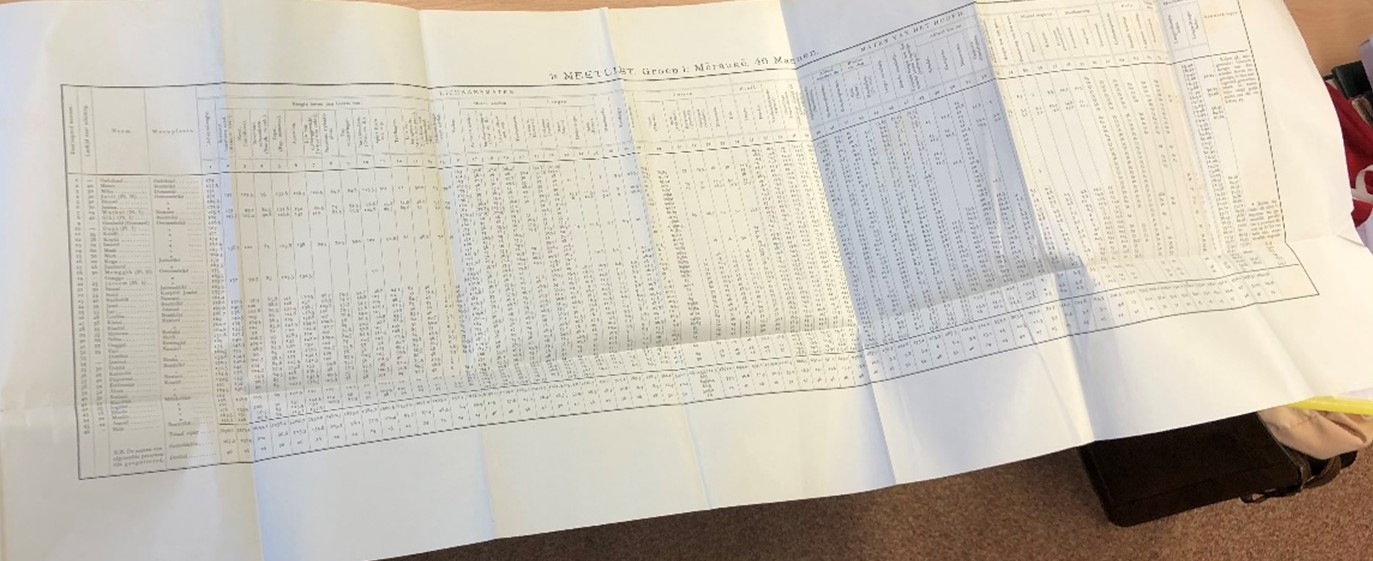

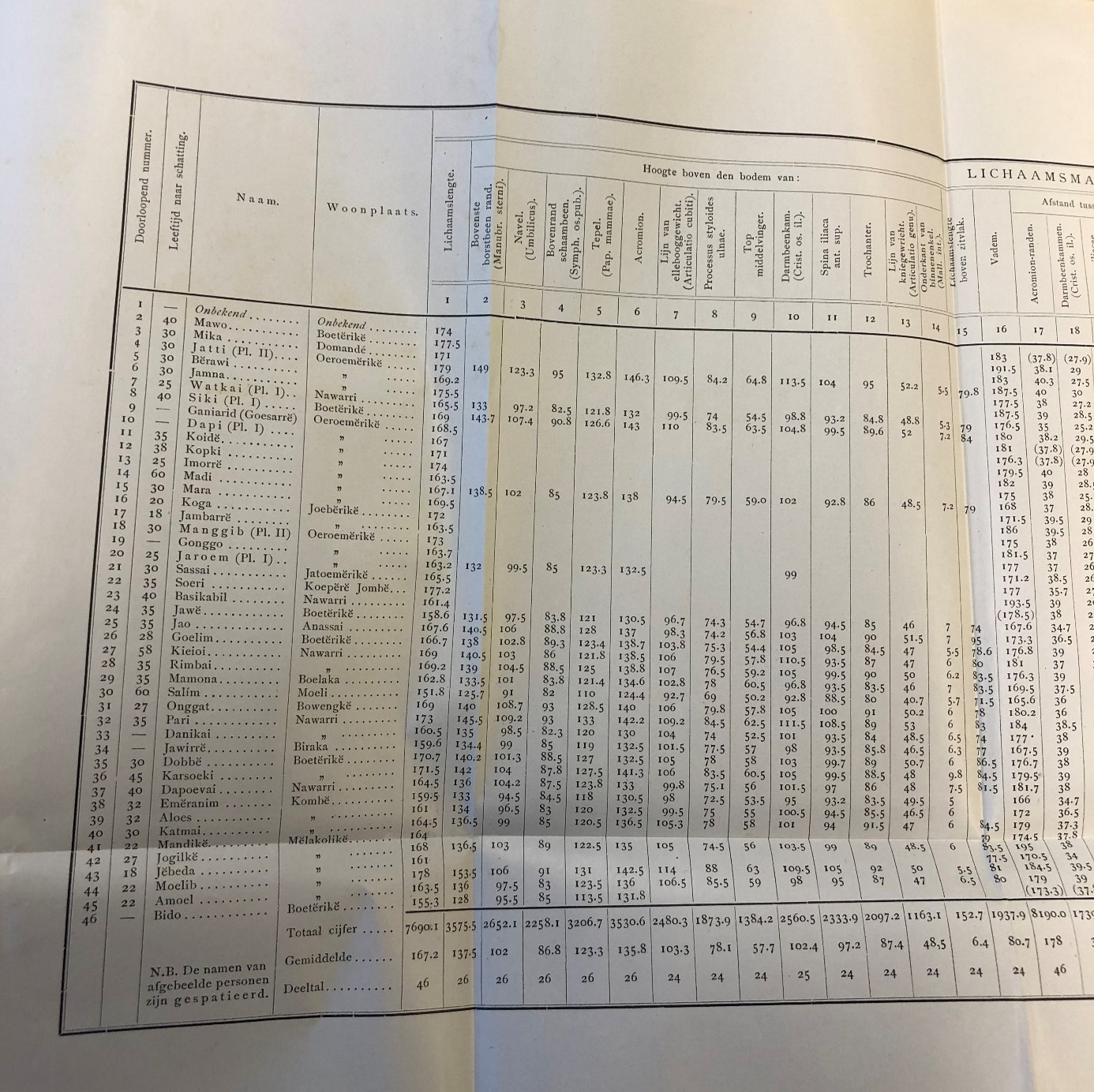

Source 2: Bido and the exploration expedition

Although we first encountered Bido as an acquaintance of the MSC missionaries around 1906, this was not his first encounter with Dutch colonialism. In their letters, the missionaries describe how Bido had acted as a guide during the 1904/1905 exploration tour led by the Royal Dutch Geographical Society (Koninklijk Nederlands Aardrijkskundig Genootschap) 6 The official report of this expedition, however, repeatedly states that there were no West-Papuan people involved in the exploration, as they were considered too ‘uncivilised’. Nevertheless, Bido is mentioned in the report, albeit not in the text: his name is included in the list of measurements of ‘men’, where he is listed as number 46 out of 46 in total. 7 However, at a height of 1,55 metres he was the shortest among the men by a distance. Additionally, his measurements were incomplete: the column indicating the estimated age of the measured person was left empty, as were most of the measurements which required specific instruments. Of the sixteen children (one girl, fifteen boys) whose measurements were recorded, the average height of a twelve-year-old boy was 1,52 metres. 8 This supports the idea that Bido was a boy in his early teens involved with the exploration tour in some way, whose data was haphazardly recorded and used to make the humble data set somewhat more substantial. This example is telling because it shows how young West Papuans were quite literally reduced to a ‘curiosity’, passive data to be ‘explored’ and ‘collected’, instead of being acknowledged as contributors to colonial enterprises.

Bido’s name is no. 46 on the list. Most measurements are missing. He was significantly shorter than most.

Although we know he was involved with the expedition, presumably as a young teenager, the sources remain silent on his exact role in the expedition.

More information might be found in the expedition archives in the National Archive in The Hague, or in the personal diaries/archives of the other expedition members.

Source 3: Moving between Marind life and colonial society

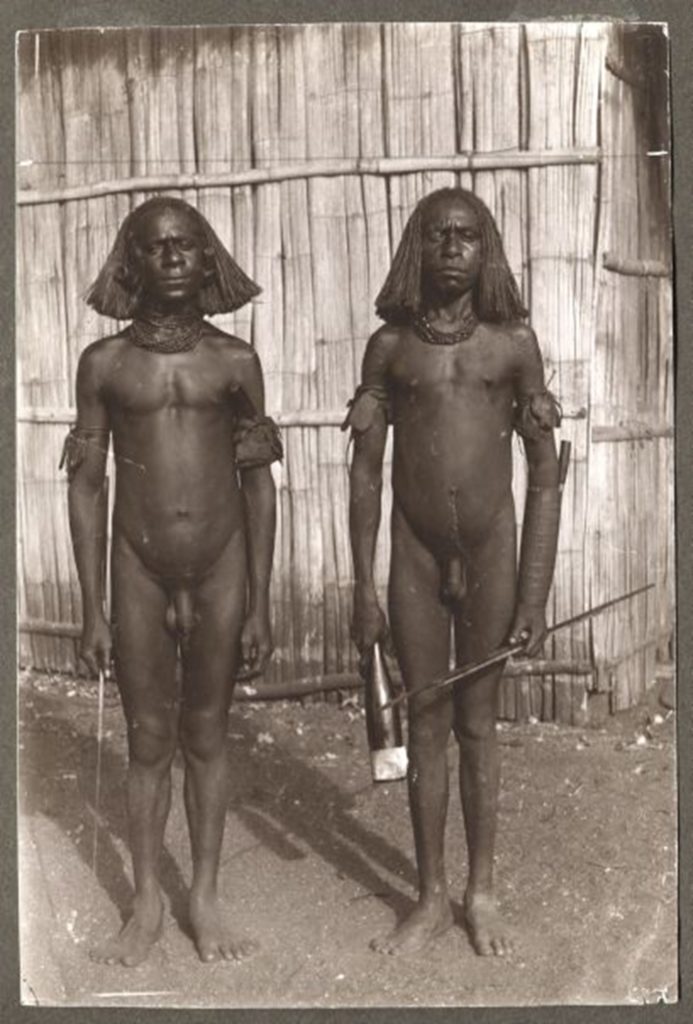

Although – according to missionary letters at least – Bido was ‘clothed’ 9 when he was a guide, he had adopted Marind dress again when he first appeared on the missionary photographs in 1906. In the image depicted above, Bido can be seen on the right.10

For the Marind-anim, dress played a role of great significance. Marind society was divided according to sharply defined sex- and age groups, each with a distinct form of dress. For the men, there were three age grades that are relevant here. The first transition took place when a boy (patur) showed the first physical signs of puberty. The patur then became an aroi-patur or ‘black boy’: his body was blackened from head to toe using a mixture of soot, and a maternal uncle was appointed as his binahor-evai,or binahor-father. The uncle acted as mentor until the boy was an adult and became his pederast.11 The aroi-patur could not boast any ornaments apart from a string of beads given to him by his binahor-father, worn around the neck, and the kimb, pieces of dried pig scrotum which were worn around the upper arms. 12 An aroi-patur could no longer live in the main village, but had to spend his time in separate encampments for young men called gotades. This age grade lasted about a year, until the boy’s hair, which was cropped short when he was a child, had grown long enough to attach artificial hair extensions to. He now became a wokraved (plural wokrevid). Other than the headdress, there was virtually no difference in the appearance of the aroi-patur and the wokraved, and they were submitted to the same rules. The wokraved age grade lasted roughly three years. When a boy had turned into a young man – when he was approximately eighteen years old – he became an ewati. At that moment, he received his first penis shell from his binahor-father, indicating that his physical growth was complete. 13 The ewati then left the gotade and returned to settle in the village.

In the earliest photographs of Bido in the missionary collection, he and his companions belong to the wokraved age grade. This is significant for at least two reasons. First of all, it shows the mobility of the first Marind intermediaries. Historical research has indicated that the first people who started working with the colonial regime often held marginalised positions in their own societies.14 However, even though Bido had joined an expedition for which he had left his village, moved out of the gotad and thereby presumably broke the ‘rules’ of his age grade, he could resume his place in Marind society afterwards. His position as wokraved shows he is still firmly rooted in Marind society.

Secondly, the photographical collection reveals that wokrevid visited the mission station frequently. What drew the boys to this settlement at the edge of the colonial town? Wokrevid and the occasional aroi-patur15 are regularly featured in photographs taken on the mission stations. Often, they seem relaxed and to be enjoying themselves, judging by their posture and facial expressions. A trip to the mission station may have been a welcome chance to get away from the gotade for a while. There are other reports in the archive in which it is suggested that the mission station sometimes functioned as a place of retreat or even as a refuge for young or vulnerable Marind.16 It was a place of exchange, where information, knowledge or Western commodities could be gained.17 For some boys and young men, like Bido, these visits may have been the start of a more permanent relation with the mission.

Source 4: starting a family at the mission station

Source: Published letter by brother G. Jeanson msc, titled ‘Eenige Kaia-kaia modellen’, in: Annalen van O.L. Vrouw van het H. Hart (Tilburg, 1911), p. 6. Original letter in: ENK, AR-P027-5007. Letter by G. Jeanson, 21 August 1910.

Transcription and translation:

Merauke, 21 Aug. 1910.

This time, I will introduce some of our Kaia-kaia’s to you. First, we have our Bido. This man already joined an expedition about five years ago, clothed, in fact, then returned to roaming in the woods like a savage, before coming back to Merauke. Ever since, he has been enjoying life in the capital and no longer fancies returning to the village, even more so now he has found a better half, who cares for it even less. He lives on our grounds now and is a hard-working man. When he is not working for us, he can be seen labouring on his own fields. It’s a shame that he has such a bad temper.

Before he had a child, his wife received quite a few beatings from him, for sleeping away the day and simply refusing to cook for her dear husband. ‘If I work’, he said, ‘you should cook’. She, however, was a piece of work as well. When the mister was raging, she would simply take his clothes and throw them on the fire or tear them to pieces.

The arrival of a little one brought some peace to the household, but the storm clouds have not vanished yet. Still, he restrains himself better nowadays and usually lets her have the final word. A fortnight ago he nonetheless lost it again and started hitting her. She simply gathered her things and fled to a neighbouring house, where he followed her and, in his rage, broke a nice lamp. It cost him dearly, as he had to pay many coconuts as compensation.

Nevertheless, they love each other dearly and these moods usually pass by quickly. After a few hours, the peace is restored and the good wife cooks a little extra for her husband, who means well after all.

By choosing to live in Merauke, Bido placed himself completely outside of Marind society. Marind who put on Western clothing were called Marind-poe-anim, literally ‘Marind-foreigners’.18 At the same time, Bido would never truly become part of the Euro-Christian community of the missionaries. In their eyes, Bido remained an inferior and ‘wild’ being, as is illustrated by the contents of the letter.

Bido and his unnamed wife are not presented as promising pioneers, but as caricatures who can barely control their own temper and urges. Still, the letter also contains a clue as to what may have motivated Bido and his wife to establish their home on the mission grounds. The letter indicates that Bido’s wife might have been the driving force behind the decision to move out of their village. In the beginning of the twentieth century, the health of the Marind-anim was declining rapidly. An initially unidentified venereal disease – identified in 1916 as granuloma inguinale or donovanosis – had caused extensive infertility, leading to a birth rate of almost zero. The disease had probably been introduced by traders from the Pacific region. Ritual sex with multiple partners was part of many celebrations and rites in Marind society, which facilitated widespread infection. The missionaries were strongly committed to finding a cure, reaching out to the media with messages of ‘extinction’.19 The missionaries argued that monogamous marriage would provide the Marind-anim with a better chance of staying healthy and producing offspring. It might have been the fear of infection which motivated Bido’s wife to move to the mission grounds.

Population and fertility decline have long been acknowledged phenomena across Oceania, signalled, for instance, by the 1922 publication of W.H.R. Rivers’ anthology Essays on the Depopulation of Melanesia. Colonial expansion is often seen as the key factor driving population decline in the region, leading to the introduction of diseases and epidemics, establishing migratory (and exploitative) colonial labour regimes, and causing alienations of Indigenous lands. Colonial discourses about ‘dying races’ usually held people (and women in particular) to be responsible for their own demise.20

Oceanians have told their own histories of epidemics and sterility-causing disease, brought to their islands by voyaging and colonising Europeans. Any perspectives or sources on fertility and (de)population in colonial West Papua or the surrounding region are welcomed.

Source 5: Definitive settlement

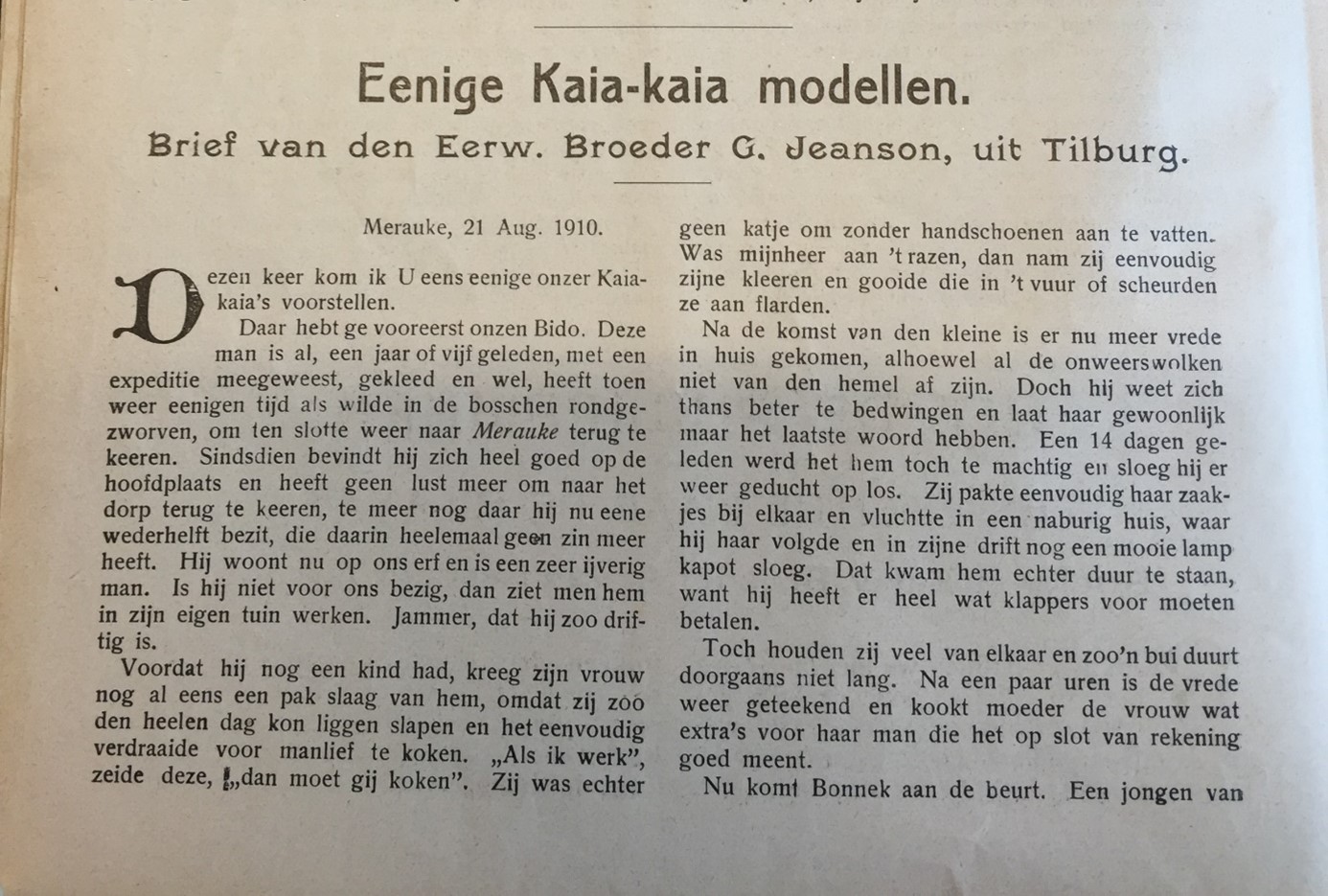

Around 1914, Bido had definitively settled with the missionaries. The photograph above was taken on the grounds of the mission station around that time. 22 The building that can be seen in the background of the photograph of Bido in uniform was actually a small hospital in which the missionaries had started treating people suffering from donovanosis. On this photograph, Bido has abandoned all forms of Marind dress, wearing a uniform-like jacket instead. His hair is short and he sports a moustache. The length of his ear lobes, however, indicates that he may have kept to wearing Marind ornaments for a long time. On the back of the photograph, a handwritten line reads: ‘Bidoe. Father of two children and has formed the first family on the grounds of the mission’.

It is often still the colonial or rather the colonialist’s archive which constructs the central narrative of the importance of colonial society. Becoming an intermediary, becoming a part of colonial society, was seen as a step forward: it was viewed as a position which brought knowledge, material benefits, and influence. This disregards, however, the position of the people like Bido in their own community.

The sources in the MSC archive have not recorded any local perspectives or voices on the positions that intermediaries such as Bido held in Marind society. Any information or contributions to this end are much welcomed.

Source 6: A new generation

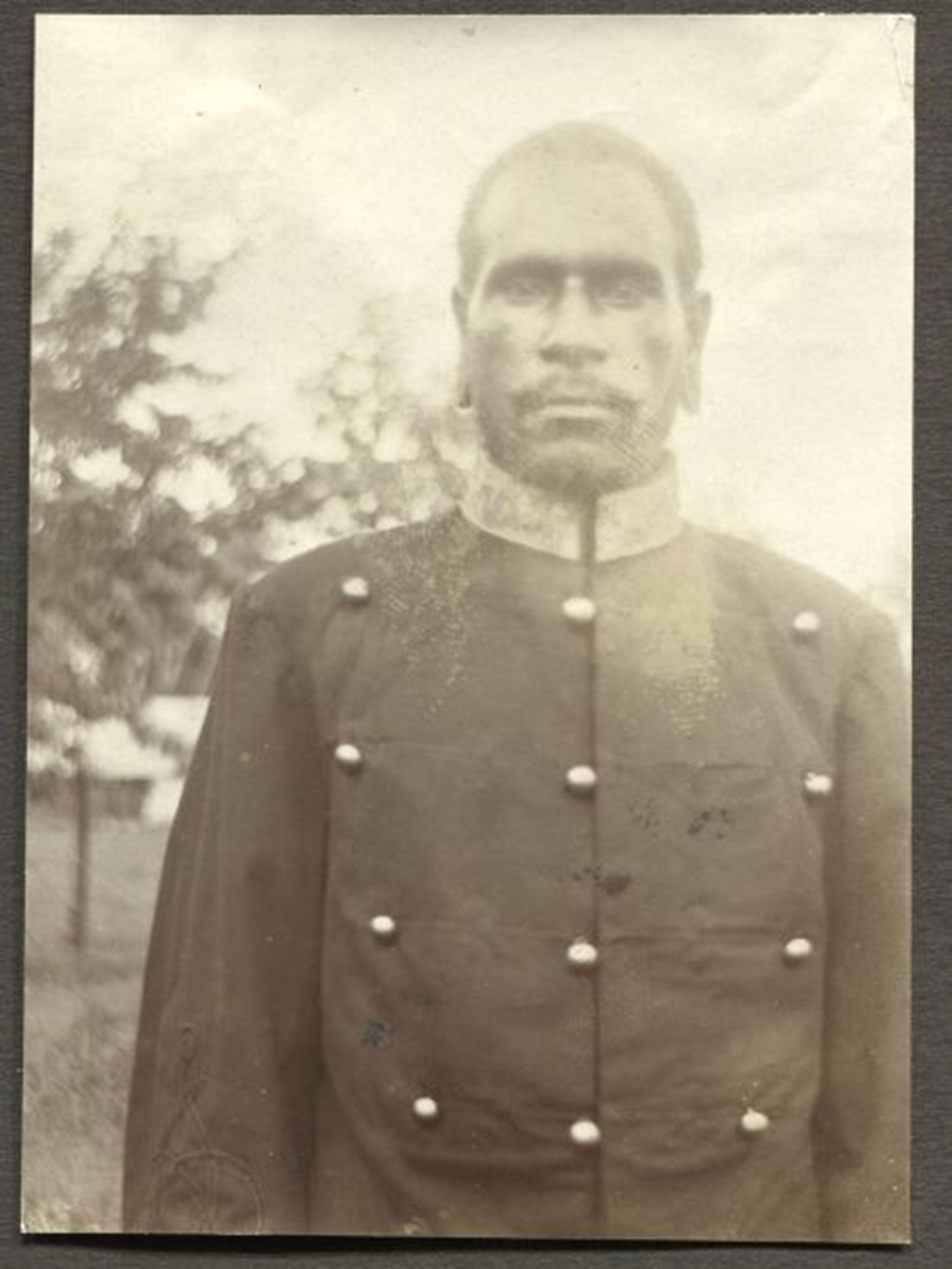

The final mention of Bido that I have found can be dated around 1923. This time it is not Bido who is depicted on the photograph, but his son.23 The boy can be seen standing in front of the presbytery of the mission station, holding a small drum. He is dressed in Marind fashion, with only two small bands around the upper arm. Someone seems to have drawn something resembling a skirt on the boy. The following is written on the back of the picture: ‘Nicolaus. Son of Bido, baptised Leo. “When I am grown, I will go and convert my people!”’24

The picture tells us many things. For one, Bido indeed stayed with the mission for a long time. Interestingly enough, this is the first time Bido is mentioned by his Christian name. One explanation for this is that the first baptisms had only taken place a few years earlier, in 1921. Many of the aforementioned sources were created before that time. The very first album, however, was composed by Verhoeven, who arrived in Merauke in 1923. The fact that both he and the inscription on this picture use the name Bido indicates that this seems to have remained his primary name.

Furthermore, the picture makes clear that Bido had at least three children (two were already mentioned on the back of the 1914 picture) while living with the missionaries, at least one of whom was baptised: young Nicolaus. Judging from his name, Nicolaus had been baptised by father Nicolaas Verhoeven, who had thus symbolically (spiritually) ‘fathered’ Nicolaus. His Christian name and the future ‘career’ spelled out for him indicate that the missionaries were involved with the next generation of Marind children from a young age onward.

In a way, with Nicolaus, this incomplete account of Bido’s life has come full circle. A new generation has arrived on the mission station, of whose life we know nothing yet. One can only wonder whether Nicolaus really went on to convert ‘his people’, or if he, like his father, would go on to live a life characterised by mobility between various social groups within colonial society.

4. Provenance of the sources

The archive of the Dutch province of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart is kept at the Erfgoedcentrum voor Nederlands Kloosterleven (ENK) in Sint Agatha, AR-P027.

5. Postcolonial continuities

Missionary interventions in family life have ongoing impact upon (gender) inequalities in the wider Pacific region.25

6. Unanswered questions and silences

Although we know Bido was involved with the expedition, presumably as a young teenager, the sources remain silent on his exact role in the expedition.

It is unknown how this history was received by local Marind communities who opted not to live at the mission station.

Little is known about the women and small children living on the mission station and their perspectives.

7. Collaboration and conversation: call for input

This vignette has been created by Marleen Reichgelt Faculty of Arts, Radboud University Nijmegen. Please contact Marleen if you have any input. By contact Marleen you will agree to the terms of conduct, to be published here.

8. Vignettes linked to this child

TBD

9. Further reading

- Geertje Mak, Marit Monteiro and Lies Wesseling. ‘Child Separation: (Post)Colonial Policies and Practices in the Netherlands and Belgium’. BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 135, nos. 3-4 (2020): pp. 4-28. https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.10871

- Gabrielle Dorren. Moved by the World: History of the Dutch Missionaries of the Sacred Heart. https://www.cti.ac.pg/uploads/4/8/2/6/4826231/dorren_g__moved_by_the_world.pdf

- Maaike Derksen. Embodied Encounters: Colonial Government and Missionary Practices in Java and South Dutch New Guinea, 1856-1942. PhD diss., Radboud University Nijmegen, 2021.

10. Author

Marleen Reichgelt MA, Radboud University Nijmegen

Marleen Reichgelt is a PhD candidate at the Department of History of Radboud University Nijmegen. Her project is centred around missionary photography, which Marleen uses to study the position, agency and lived experiences of children engaged in the Catholic mission on Netherlands New Guinea between 1905 and 1962. Her core research interests are intercultural contact and exchange in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth century, involving three overlapping fields: photography and visual culture; (Dutch) colonialism and postcolonialism; and the Catholic mission.

Notes

- The name is spelled as both ‘Bido’ and ‘Bidoe’ in the sources. For consistency, I have opted to use the name Bido throughout this vignette.[↩]

- ENK, AR-P027-20153. ‘Marind jongens – met hond is Bido – hoofd eerste groep gedoopten’.[↩]

- The archive of the Dutch province of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart is kept at the Erfgoedcentrum voor Nederlands Kloosterleven (ENK) in Sint Agatha. The reference numbers are AR-P027-20152 and AR-P027-20153.[↩]

- In Dutch: ‘Nieuw Guinea 1905-1922, Oorspronkelijke bewoners van de Zuidkust van Nieuw Guinea rond 1910 Plus enige andere foto’s’ and ‘Marind N. Guinea 1910-1923, Oorspronkelijke bewoners van de zuid kust van Nieuw Guinea, de Marind stam rond 1910’. All translations are by the author.[↩]

- The vast majority of the captions date the photographs to 1910. However, almost all photographs in the album must have been taken in the period 1906-1908, because a) Nollen and his camera left after 1909 and b) many photographs were reproduced in publications appearing between 1907 and 1909.[↩]

- ENK, AR-P027-5007. Letter by G. Jeanson, 21 August 1910.[↩]

- Rouffaer, Seyne Kok and Adriani, De Zuidwest Nieuw-Guinea-expeditie 1904/5, pp. 397-398: ‘1e meetlijst’.[↩]

- Rouffaer, Seyne Kok and Adriani, De Zuidwest Nieuw-Guinea-expeditie 1904/5, ‘2e meetlijst’.[↩]

- Probably wearing some form of Western clothing or textile covering at least the pubic area. Even though the Marind-anim had a complex system of dress, it deviated from the Euro-American norm that one’s genitalia must always be covered when in public, and, therefore, the Marind-anim were considered ‘naked’ or ‘undressed’ according to Euro-American cultural expectations.[↩]

- ENK, AR-P027-20153.[↩]

- Jan van Baal, ‘Dialectics of Sex in Marind-Anim Culture’, in Ritualized Homosexuality in Melanesia, ed. Gilbert H. Herdt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), p. 132.[↩]

- Jan van Baal, Dema: Description and Analysis of Marind-Anim Culture (South New Guinea) (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1966), p. 146.[↩]

- Van Baal, Dema, p. 135.[↩]

- William Gervase Clarence‐Smith, ‘The Redemption of Child Slaves by Christian Missionaries in Central Africa, 1878-1914’, in Child Slaves in the Modern World, ed. Gwyn Campbell, Suzanne Miers and Joseph C. Miller (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2011), p. 180.[↩]

- Unlike the wokrevid, aroi-paturs were usually pictured together with adult men – most likely their binahor-fathers who accompanied them. Wokrevid seem to have visited the mission stations mostly in pairs – there are only a few photographs in the collection which depict a single wokraved.[↩]

- The missionaries reported an incident in which a group of boys were caught seeing a forbidden ritual. In fear of repercussions, they stayed with the missionaries on the mission station for some weeks.[↩]

- Ingie Hovland, Mission Station Christianity: Norwegian Missionaries in Colonial Natal and Zululand, Southern Africa 1850-1890 (Leiden: Brill, 2013), p. 133.[↩]

- Mgr. N. Verhoeven msc interviewed by brother Frans van den Berg, 8 June 1977. Nijmegen, Katholiek Documentatie Centrum, Archive KomMissieMemoires, 555.[↩]

- Petrus Vertenten msc, ‘Zuid-Nieuw-Guinea sterft uit’, Java-post, 27 June 1919. The trope of saving people from supposed extinction was used by missionaries all over the world, see also: Larry Prochner, Helen May and Baljit Kaur, ‘“The blessings of civilisation”: Nineteenth-Century Missionary Infant Schools for Young Native Children in Three Colonial Settings – India, Canada and New Zealand 1820s-1840s’, Paedagogica Historica 45 (2009), p. 85.[↩]

- On these discourses and missionaries use of medicine as a tool for colonial governance, see: Hyaeweol Choi and Margaret Jolly (eds.), Divine Domesticities: Christian Paradoxes in Asia and the Pacific (Canberra: ANU Press, 2014).[↩]

- Original Dutch text: ‘Bidoe. Vader van twee kinderen en het eerste gezin heeft gevormd op het erf v.d. missie’.[↩]

- ENK, AR-P027-20210. Second folder, photograph no. 228643.[↩]

- ENK, AR-P027-20210. Second folder, photograph no. 228748.[↩]

- ‘Nicolaus. z.v. Bido, gedoopt Leo. “Als ik maar eens groot ben, dan ga ik mijn volk bekeeren!”’[↩]

- See: Nicholas Bainton, Debra McDougall, Kalissa Alexeyeff, and John Cox (eds.), Unequal Lives: Gender, Race and Class in the Western Pacific (Canberra: ANU Press, 2021). https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1h45mj4[↩]

Bido as guide for KNAG exploration tour

Bido frequents the mission station

Bido and his wife settle on the mission station

Nicolaus, son of Bido is born